Clifford found his Jordanaires in Holland.

Personnel

Clifford Jordan (tenor saxophone), Cees Slinger (piano), Ruud Jacobs (bass), Han Bennink (drums), Steve Boston (percussion); Jacques Schols (bass), Martin van Duynhoven (drums)

Recorded

on September 10, 1969 at VARA studio, Hilversum; on June 3, 1970 at Paradiso, Amsterdam

Released

as NJA 2401 in 2024

Track listing

Vienna

Impressions Of Scandinavia

Doug’s Prelude

Quagadougou

Girl, You’ve Got A Home

I Can’t Get Started

The Girl From Ipanema

Unmistakable tone defines the greats, whether it’s icons like Lester Young or John Coltrane or acquired tastes like Lucky Thompson or Clifford Jordan. You’ll spot Jordan in a cacophony of thousands. Lovely tone. Clear as a blue sky, pure as goat’s milk. His tone is a precious satin cloth that traveled westward through the Silk Road. A touch of the blues. A dog’s wail from the back porch.

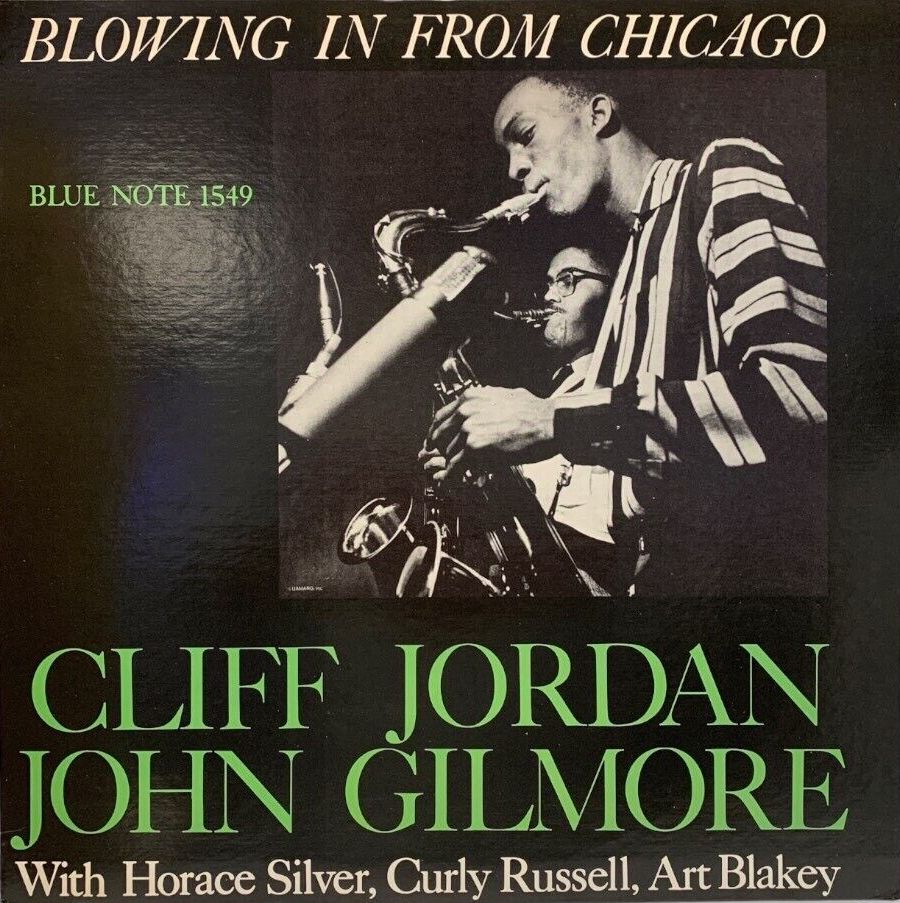

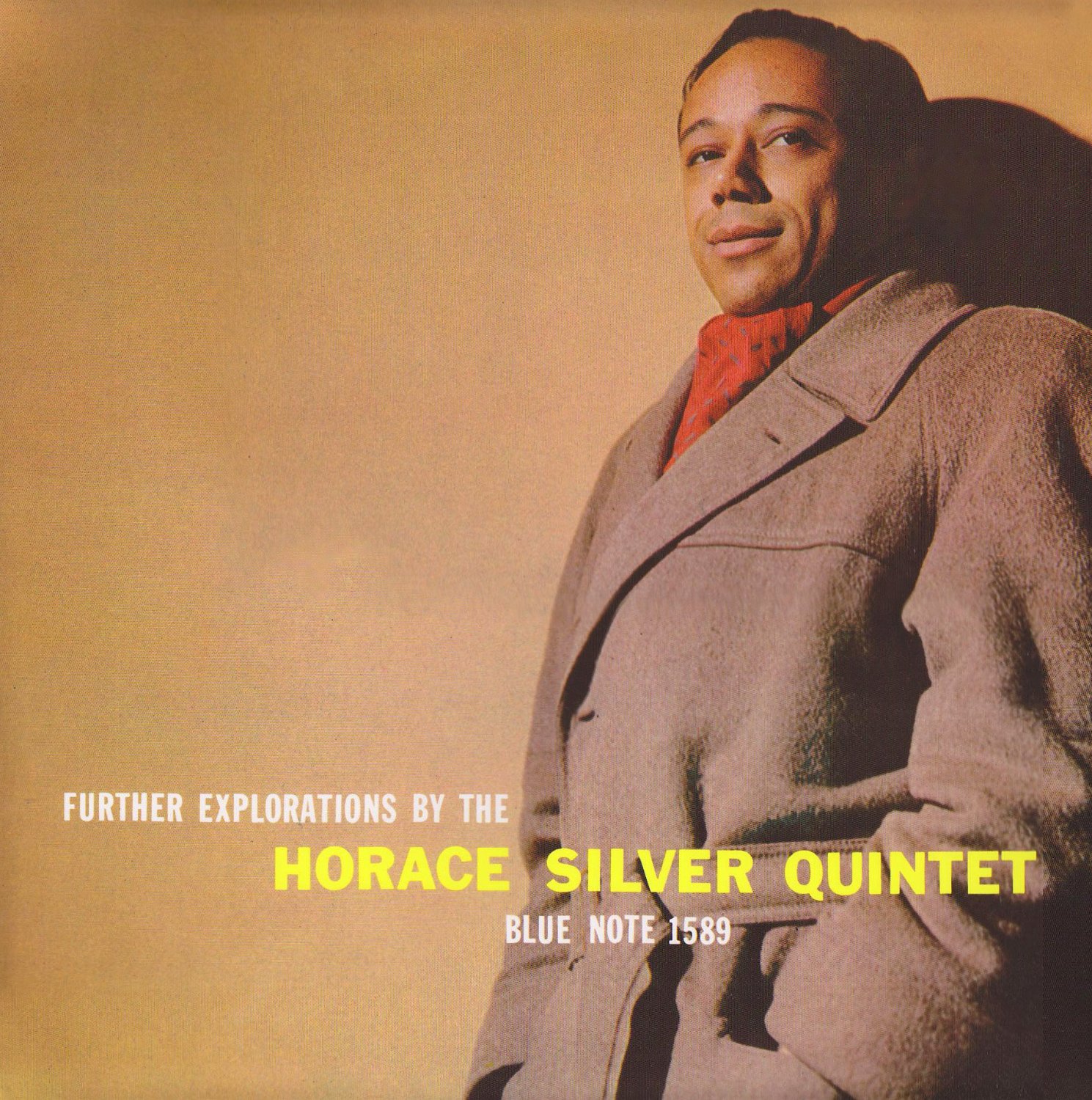

Chicago-born. Middle name: Laconia. This is also the title of an exciting Latin-tinged tune from his fourth Blue Note debut album Cliff Craft from 1957. Jordan was a promising, Rollins-inspired tenor saxophonist who found himself a spot in the vanguard of hard bop, recording with Art Blakey, Lee Morgan, Horace Silver and Max Roach.

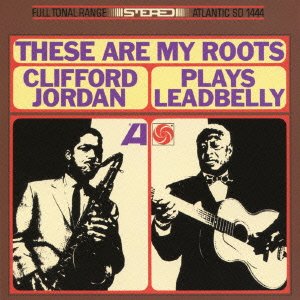

As the years went by, Jordan followed a progressive route, playing with Charles Mingus in the 1960’s alongside Eric Dolphy. He was interested in the movement of black rights and consciousness. Typically, Jordan wanted to take matters in his own hands and produced recordings of favorite artists and himself under the heading of The Dolphy Series. Though his efforts of releasing those tapes by himself stranded, his recordings eventually found a home on the groundbreaking Strata-East label from Stanley Cowell and Charles Tolliver. Jordan’s participation in Strata-East and influence on the avant garde is a feat that is too often neglected.

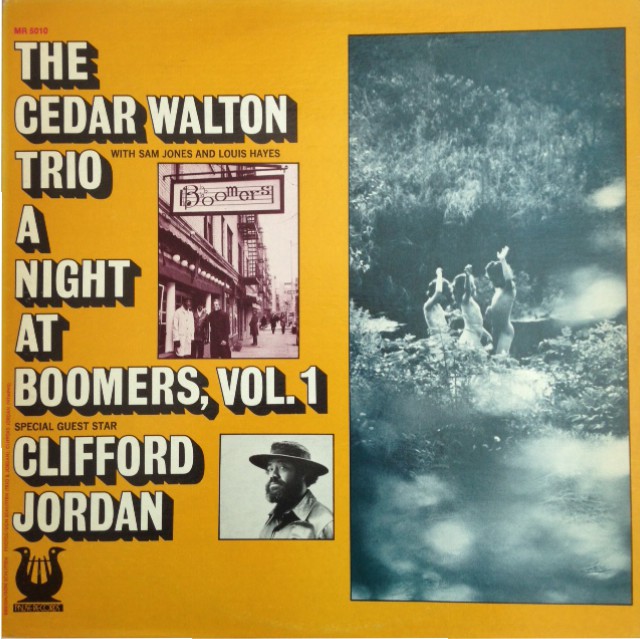

Glass Bead Games, often cited as a perennial favorite by jazz fans and a major inspiration to following generations of players, was released by Strata-East in 1973. Part of that album represented the start of a stellar quartet that would come to be known as The Magic Triangle: Jordan, Cedar Walton, Sam Jones and Billy Higgins.

A year before, Strata-East released In This World, a set of original tunes by Jordan from 1969, featuring Don Cherry, Kenny Dorham, Julian Priester, Wynton Kelly, Richard Davis and drummers Ed Blackwell, Roy Haynes and Albert Heath.

It is the repertoire of In This World that, among others, is played by Jordan on a top-notch new release by the Dutch Jazz Archive: Beyond Paradiso. Jordan was booked to play in Paradiso, Amsterdam’s hub of the counterculture movement in 1969, but the club was closed for a month due to circumstances and Jordan and his band of Dutch stalwarts – pianist Cees Slinger, bassist Ruud Jacobs and drummer Han Bennink – were transferred to the VARA studio in Hilversum. A year later, Jordan was offered a second chance and played in Paradiso with Slinger, bassist Jacques Schols and drummer Martin van Duynhoven.

The Hilversum date is positively explosive. Jordan presents a ballad, Doug’s Prelude, a hip blues line, Quagadougou, and Vienna and Impressions Of Scandinavia, both enticing modal canvases, open for a lot of suggestions, and everybody rises to the occasion, Slinger in a McCoy/Herbie-inspired role and the tandem of Jacobs/Bennink notably propulsive. At times, Jordan wails like a gladiator to the gods, but, typically, he always remains in balance, flowing with long graceful lines. There never is any strain, a great feat. As liner note writer Tom Beek says – he did a great job by the way – Jordan is quite the king of understatement.

At Paradiso, though the sound, not surprisingly, is a bit dry and muffled, Jordan kept up his charged but balanced playing and, this time, plays the standards I Can’t Get Started, The Girl From Ipanema and Jordan’s Girl, You’ve Got A Home, the latter, which applies to the whole program of Beyond Paradiso, making abundantly clear that the Dutch cats convincingly stood their ground.

In this world, better said, flood, of archival releases, this applies to the Dutch Jazz Archive as well.

Clifford Jordan

Buy Beyond Paradiso at Nederlands Jazz Archief here.

The Vara show is also available on vinyl.