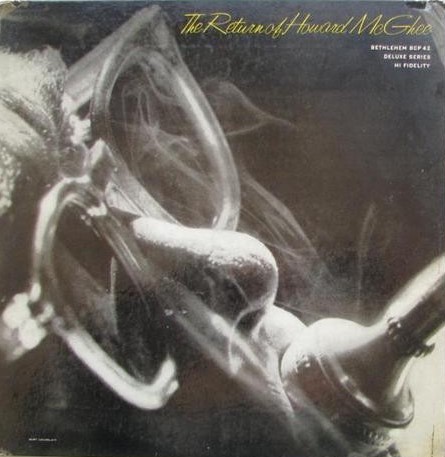

Howard McGhee returned to Bethlehem. A glorious entrance.

Personnel

Howard McGhee (trumpet), Sahib Shihab (baritone saxophone, alto saxophone), Duke Jordan (piano), Percy Heath (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

Recorded

on October 22, 1956 in New York City

Released

as BCP 42 in 1956

Track listing

Side A:

Get Happy

Tahitian Lullaby

Lover Man

Lullaby Of The Leaves

You’re Teasing Me

Transpicious

Side B:

Rifftide

Oo-Wee But I Do

Don’t Blame Me

Tweedles

I’ll Remember April

By 1956, trumpeter Howard McGhee already was a veteran of bebop and one of the earliest collaborators of Charlie Parker, The One, The Kick Start of modern jazz. More than a colleague, he was a friend. Howard McGhee was born in 1918 and two years the senior of Charlie Parker. Now and then, the Tulsa, Oklahoma-born trumpet player helped out Parker, saxophoniste maudit, who continuously ran into trouble.

Sign of the (ominous) times: In 1946, Charlie Parker had completed his first recordings for Ross Russell’s Dial label in Los Angeles. McGhee lived in Los Angeles with his wife Dorothy. They were a mixed couple that was continually harassed by the L.A. police force. At one time, the vice squad planted drugs in their apartment and promptly arrested McGhee. Parker was in bad shape, living in a garage on McKinley Avenue, his daily diet solely consisting of port wine. The McGhee’s took him to their apartment. Howard and Dorothy, against the grain, opened a little jazz club on the premises of the defunct Finale club and booked Charlie Parker.

The first thing one notices is that The Return includes Lover Man and Don’t Blame Me, two standard ballads identified by influential renditions by Charlie Parker. Lover Man, Dial 1946, was a sinuous exercise – notwithstanding the fact that Parker was sick and close to a nervous breakdown, awoken just in time by the sounds of his colleagues to pick up on the melody, which perhaps was one of the reasons Parker abhorred this version. McGhee, himself a trumpeter who inspired many of the up-and-coming players of the hard bop era, was the trumpeter on that recording and continued to perform Lover Man for the rest of his life.

Furthermore, McGhee’s group includes pianist Duke Jordan. Jordan was part of one of Parker’s most steady groups of 1947-48, which also included Miles Davis, Tommy Potter and Max Roach. The bop-oriented The Return Of Howard McGhee – McGhee had been off the scene a while as a consequence of his use of narcotics – also featured alto and baritone saxophonist Sahib Shihab, bassist Percy Heath and drummer Philly Joe Jones. Both Shihab and Jones had occasionally played with Parker.

The chemistry – no pun intented – is striking. The group performs as a bunch of buoyant teenage pals at play in the lake, two diving from the bridge, one showing his prowess as a crawler in clear sight of nearby feminine onlookers, another shouting crazy things to fly-over goose. Not a wild bunch of hooligans, but charged and charming. So Get Happy makes perfect sense. And the old warhorse is exemplary of a great album that is too easily overlooked. There’s the rare sparkle and bite of Philly Joe Jones. The smooth blend of McGhee’s exuberant, sinuous trumpet and Shihab’s pretty spectacular baritone sax. The spry and gracefully fashioned solo’s of Duke Jordan.

The group performs eleven tunes, including the soft-hued, hypnotic Lullaby Of The Leaves, the catchy, Latin-ish and uptempo I’ll Remember April and the sizzling flagwaver Rifftide. Lover Man is excellent, the coupling of McGhee’s sly variations on the melody and delicate bittersweet comments with the bright and full-bodied tone that’s reminiscent of Louis Armstrong is very attractive. The long life already lived, from his stints with Count Basie and Charlie Barnet, to the laboratory of Minton’s Playhouse and ‘carvin’ with the bird’ signifying a weathered and stellar jazz artist.

A set of eleven tunes that rarely stretch beyond four minutes – unfortunately – suggests that Bethlehem was aiming at radio airplay, perhaps inspired by the success of the Mulligan/Baker group of Pacific Jazz. Bethlehem wasn’t strictly a jazz label. Nonetheless, its jazz discography has slowly but surely turned into a special place for jazz freaks, like that little superb Juarez burrito joint for Texan lovers of hot Latin cuisine. The great engineering can compete with Rudy van Gelder as well as Roy DuNann from Contemporary, the label on which McGhee recorded two more successful albums in 1960. To boot: you ever seen such a beautiful sleeve? In the words of Babs Gonzales: exboopident!