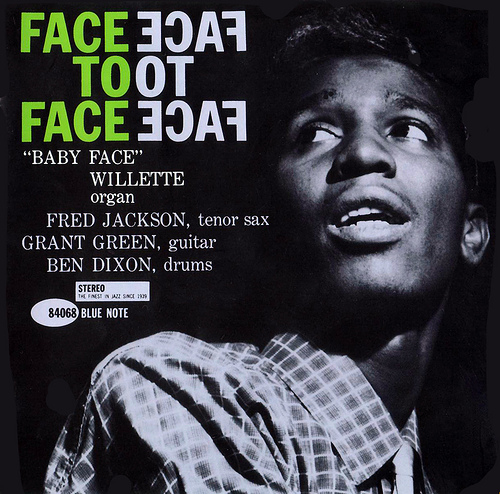

It was a busy week for organist Baby Face Willette, the last week of January, 1961. In fact, the three sessions Willette was involved in – sessions for Lou Donaldson and Grant Green and the leadership date of Face to Face – account for half of the organist’s discography. One may conclude Willette is something of a footnote in jazz history. As his best album, Face To Face, however, proofs footnotes usually don’t come that exciting.

Personnel

Baby Face Willette (organ), Fred Jackson (tenor saxophone), Grant Green (guitar), Ben Dixon (drums)

Recorded

on January 30, 1961 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Released

as BST 84068 in 1961

Track listing

Side A:

Swingin’ At Sugar Ray’s

Goin’ Down

Whatever Lola Wants

Side B:

Face To Face

Something Strange

High ‘N’ Low

Lou Donaldson certainly was of that opinion. In reference to the session for Donaldson’s

Here ’Tis, the popular alto saxophonist is quoted as saying (he also mentioned accompanists Grant Green and drummer Ben Dixon):

“These guys have all played a lot of rhythm and blues and they know what it’s about.” Lou Donaldson brought Grant Green to the attention of Blue Note’s Alfred Lion in 1960. Green was steeped in r&b and influenced by Charlie Christian. Together they met Willette in New York. Before turning to jazz, Willette had worked in a variety of r&b settings. Tenor saxophonist Fred Jackson worked with Little Richard, B.B. King and had been part of r&b-singer Lloyd Price’s outfit. Drummer Ben Dixon also played in that group.

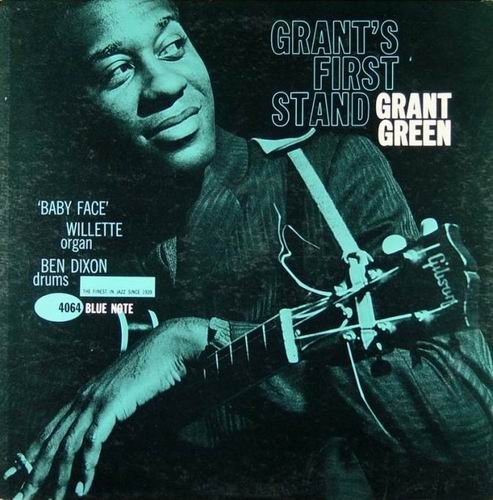

Here ’Tis stems from January 23, Grant Green’s Grant’s First Stand (also including Ben Dixon) was recorded on January 28 and the Face To Face-session took place on January 30. It indeed is about the blues or has a blues-based format. Willette penned five catchy originals. Willette’s edgy sound, a combination of a plucky percussion-setting and slight vibrato, is mesmerising. Style-wise Willette uses a number of tricks from Jimmy Smith’s bag. Putting heat into a solo, stretching over bars by way of a suspended left hand chord and freewheeling right hand, is one of them. He uses it in Whatever Lola Wants and Swingin’ At Sugar Ray’s. The latter is a sassy tune on which Grant Green gets into the picture with some trademark, throat-grabbing blues licks. His sound is unusually distorted on this tune, which unfortunately draws the attention away from the rest of his statements.

Willette does a great job of avoiding blues clichés. His lines are jumpy and fresh. Rarely at a dead end, one can hear the pleasure Willette takes in putting something surprising and funky in each new chorus. Willette carefully builds momentum on the slow, down & dirty blues Goin’ Down. Tenor saxophonist Fred Jackson delivers a juicy and humorous piece of rock ‘n’ jazz. His solo is lively, direct and consists of long wails that alternate with short, breathy puffs, valve effects and speedy, big-toned figures that bear the mark of Coleman Hawkins and Gene Ammons.

The title track, Face To Face, is an uptempo, stop-time tune cleanly executed by the rhythm section. (including the bass Willette provides) Ben Dixon lays down a driving shuffle in the middle section that finds all soloists in fine form. Whatever Lola Wants is the only non-Willette composition. It has a very danceable, exotic rhythm. Willette cooks, Jackson variates nicely on the theme; the element of surprise inherent in Jackson’s work is a strong asset of Face To Face. Green doesn’t really break out of his routine phrasing. Clearly, on Whatever Lola Wants, Fred Jackson’s got the better of him.

The album ends on a satisfying note. Something Strange and High ‘N’ Low aren’t standout tracks, but fine blues cuts. In the second part of his recording career – the 1964 albums Behind The 8-Ball and Mo-Roc for the Argo label – gospel and Carribean themes were highlighted more than on his Blue Note recordings. The albums show a full-grown identity and have their moments, but are inferior to Face To Face. They lack drive and the abilities of the high-quality personel that was present on Face To Face and his other Blue Note recording from 1961, Stop And Listen.

The liner notes of Face To Face refer to the wanderlust that had been characteristic of Willette’s personality ever since he was a kid. This penchant for traveling also accounted for his occasional disappearance from the scene and obscurity from the public eye after 1964. Ultimately, failing health led to his decease in 1971. Could Willette have been a new organ star contending with Jimmy Smith and Jimmy McGriff? No doubt. Baby Face Willette had the chops, and the looks. Face To Face was a promising start. It, however, was also very short to the finish.