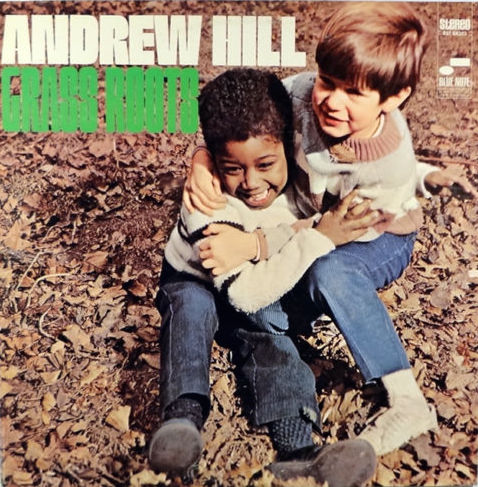

One of the most accessible albums of pianist Andrew Hill’s imposing stretch of Blue Note releases in the sixties, 1968’s Grass Roots is still a thoroughly challenging affair.

Personnel

Andrew Hill (piano), Lee Morgan (trumpet), Booker Ervin (tenor saxophone), Ron Carter (bass), Freddie Waits (drums)

Recorded

on August 5, 1968 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Released

as BST 84303 in 1968

Track listing

Side A:

Grass Roots

Venture Inward

Mira

Side B:

Soul Special

Bayou Red

Hill, who had one foot in the avantgarde, one foot in the mainstream, never received the kind of recognition like pianists Herbie Hancock and McCoy Tyner but was highly acclaimed by serious jazz fans and critics. Though more under the radar, the pianist, who passed away in 2007, tread a similar path of the creative elder statesman who’s admired for legendary recordings on Blue Note in the sixties. Mention Black Fire, Point Of Departure or Judgment to any self-respecting, avant-leaning jazz fan and goosebumps will start to pop up on his/her arms like ants on a smashed lollypop on the sidewalk. 24-carat classics in which rhythm, harmony and melody are altered extremely in order to find fresh ways of expression. Hill doesn’t buy the method of discarding them for the sake of freedom, which turns out to be illusionary anyway, but favors a bottom-up approach: change through evolution. In this regard, the title of Grass Roots is telling.

Cerebral, introspective. Call his style what you like, at any rate, Hill’s notes cannot but have a strong pull on the listener. If notes are words, Hill is describing a descent into the mysterious abyss of the mind. A labyrinth of ephemeral sensations, a place Hill searches and researches like a child a playground. The playground isn’t necessarily dark and damp, the search is intense but strangely uplifting. For Hill, life is sweet, sour, a ‘dance macabre’. And his yearning to explore it is the essence of his art.

A ‘pianistic’ intellectual? Certainly not. Hill’s longing is also firmly focused on rhythm, the root of his trade – jazz. Hill’s beats are clever, complex constructions that nonetheless often remain surprisingly close to the toe-tappin’ sounds commonly flowing out of a Harlem BBQ joint. His penchant for playing against the rhythm is evident in Bayou Red, a modal piece with majestic solo statements by the bandleader. Hill’s other modal tune, Venture Inward (yes, do!) boasts sparse, dense chords that are accompanied by meandering lines which are spiced with, sometimes sliced by, clusters of seemingly jangling but remarkably precise notes. How nice to be ‘out’, ‘in’, ‘in’, ‘out’, ending up with the best of two worlds, like the kid daughter with a dollar who said ‘no’ to daddy when he asked her if mom’d given her the pocket money.

The concise, hip line of Grass Roots has a circular nature, like a viper who keeps biting his tail. The compositions has a sly groove and finds Hill in elegant form. Soul Special’s a boogaloo, Hill-style, the measures slightly differing from the standard blocks of eight. The bunch that gathered at Van Gelder Studio on August 5, 1968 proves sensitive to Hill’s needs. It’s a major league crew. Ron Carter and drummer Freddie Waits, a versatile drummer who, for instance, played on both Ray Bryant’s 1966’s soul jazz gem These Boots Are Made For Walkin’ and Richard Davis’ deconstruction of Bird and Monk, the 1973’s Muse album Ephistrophy/Now’s The Time, are obviously enjoying the extended chord of Bayou Red’s A-part, hanging on to it like a windsurfer to his sail, subsequently relishing the release with booming, sizzling fills. Carter would continue his collaboration with Hill, playing on the subsequent albums Lift Every Voice and Passing Ships.

Lee Morgan attunes nicely to the repertoire. Generally heated, Morgan alternates his fiery approach with subdued toyings with the beat and measured valve effects, particularly in Soul Special. His bright ensemble playing with Booker Ervin lingers in the mind. Booker Ervin’s lines in Bayou Red make up the musical equivalent of a snake that dances in the basket of a Punjabi snake charmer. Ervin, Mr. Blues Wail, the roaring, advanced player who came into prominence with Charles Mingus in 1959, is relatively subdued, perhaps under the influence of the bandleader’s organic jazz menu. Bon appetit, this dish is the bomb.