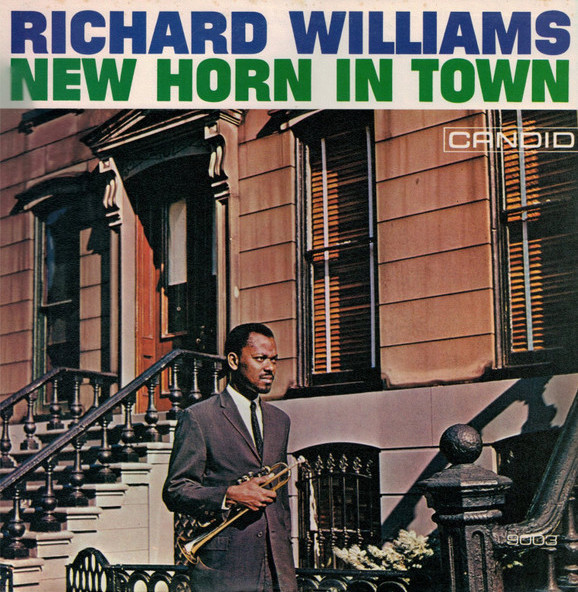

The rather overlooked trumpeter Richard Williams boasts an impressive discography, regardless of just one album as a leader, New Horn In Town. A rare Dutch interview reveals that Williams could certainly turn a phrase.

Personnel

Richard Williams (trumpet), Leo Wright (alto saxophone, flute), Richard Wynands (piano), Reggie Workman (bass), Bobby Thomas (drums)

Recorded

on September 27, 1960 at Nola Penthouse Studio, New York

Released

as Candid 8003 in 1961

Track listing

Side A:

I Can Dream Can’t I

I Remember Clifford

Ferris Wheel

Raucous Notes

Side B:

Blues In A Quandary

Over The Rainbow

Renita’s Bounce

1960 was a very good year. A productive hard bop year with excellent releases from Horace Silver, Art Blakey and Cannonball Adderley and a period of challenging and game-changing efforts from John Coltrane, Bill Evans and Ornette Coleman. It was a fine trumpet year. Lee Morgan came of age, blazing and burning, Donald Byrd was making a name for himself, darling of the press Miles Davis was in between Kind Of Blue and Sketches Of Spain (not bad). Everybody loves to play the trumpet. Its three valve-system is relatively ‘uncomplicated’, it’s a forthright emotive tool and portable to boot! There were plenty of excellent trumpeters that tried to gain a foothold or solidify their position, among others Joe Gordon, Dizzy Reece, Paul Serrano, Freddie Hubbard, Blue Mitchell, Kenny Dorham and Art Farmer.

Then there was Richard Williams, one of many. Writer Nat Hentoff strived to put Williams in the limelight and produced a record for his short-lived Candid label, New Horn In Town. (note: Hentoff also turned his attention to another excellent trumpeter, Benny Bailey and released Big Brass in the same year; New Horn In Town is Williams’ only record as a leader.

There’s a whole story to be told before ánd after Williams’ solo album from 1960. (A very good one featuring alto saxophonist and flutist Leo Wright, pianist Richard Wynands, bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Bobby Thomas; the frontline ensemble sound of Williams and Wright is like good cappuccino, vanilla and citrus flavors topped off with full cream milk, the sound of Williams is brassy and marked by joie de vivre, Wright’s tone is darker and edgy, Williams has a forthright and stately delivery, Wright seems more introverted and self-absorbed, perhaps a difference between swing and bop but anyhow blending smoothly ; I Can’t Dream Can’t I is Californian breeze and Williams beautifully and daringly weaves through the high register, ballad’s Over The Rainbow and Benny Golson’s I Remember Clifford are stately yet imbued with the blue bended notes of Williams, Williams’ self-penned Raucous Notes is fast burning bop and his Renita’s Bounce equates with bubbling and boiling gumbo and tunes and performances by Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers circa Clifford Brown/Lou Donaldson; a few examples from a top-rate hard bop record)

Before: Williams was born in Galveston, Texas in 1931. His parents were from New Orleans. Bunk Johnson was a family friend. (“For me he was just an old trumpet player. It was only later that I realized that much of his stories about his important role in jazz was true.”) The sanctified church and high school got him acquainted with music and instruments, Louis Jordan, Illinois Jacquet, Lester Young, Fats Navarro and Dizzy Gillespie got him into jazz. Williams worked in territory bands and r&b outfits in the late 1940’s, was part of army bands in the early 1950’s alongside Cedar Walton, Don Ellis, Ronnie Scott and Dizzy Reece and strengthened the ranks of the Lionel Hampton band in 1956. He arrived in New York and recorded with Booker Ervin, Gigi Gryce, Oliver Nelson, Yusef Lateef and Randy Weston. And Charles Mingus. In the interview in the Dutch magazine JazzNu from October 1979 which provided much of this information, Williams, like many before or after him, mentions not only the demanding and musically profitable Mingus ‘method’ but also the bassist and composer’s extra-curricular outburts. (“I’ve never been the subject of his fury, it was more like the other way around! Once at the Newport Festival, he let the band stop in the middle of a tune, focused on the audience and went into blind rage. It was disgusting and I walked away from the stage. Man, I could tell you stories but I rather won’t.”)

After: Williams played on Mingus Dynasty and Pre-Bird (technically ‘before’ his solo album, as they were recorded in 1959 and early 1960), Mingus Mingus Mingus and Black Saint And The Sinner Lady, quite a resumé. Williams was part of the Duke Ellington band in 1965 and an original member of the famed Thad Jones/Mel Lewis orchestra from 1966 till 1969. As jazz fell on harder times, Williams worked in musicals and at the Radio City Symphony, played in Latin and Mickey Mouse bands, cooperated with Sun Ra and produced jingles. He says about his style and versatility: “Miles Davis must have been an influence through osmosis. You’re unable to avoid such a strong personality. I probably adapted to circumstances because this is a prerequisite of working in big bands. And as you get older and mature you realize that it’s not about the quantity of notes. Whatever situation I’m involved in, I always try to express my feelings. I never prepare solos on different tunes, because I want to remain spontaneous.”

In 1979, the New York loft scene raised a fuzz and was seen as a restart of jazz. “Lofts? Some don’t have a clue about the workings of their instrument. Suddenly you read in the papers that one or another has achieved something extraordinary. It’s like a joke, even the lauded cat is having a laugh. I’ve played with people that didn’t even know when a chorus ends. It’s like giving a monkey a trumpet for Christmas and seeing what happens.”

Williams was put in the spotlight by bop trumpeter and avant-leaning composer Nedly Elstak at the International Jazz Festival Laren. A special broadcast was made by VARA. Musicians were in the know. But the attention of the general audience had generally eluded Williams. How come? “If only I knew. You have to play the game, presumably? It doesn’t have anything to do with music. Maybe I don’t have star personality. I never impose myself upon others. It also depends if anyone is willing to back you up. Take Dexter Gordon. He was doing the same thing for thirty years when CBS pushed him into the market and that was that.”

“You have to realize that the American power system sees music as a commodity. It is sold just like a can of beans, depending on packaging and advertising, all that stuff. Here in Europe it’s different, it’s not the land of milk and honey but at least jazz is respected as art. I’ve been thinking about settling down here, but I have a family and it’s not that easy.”

Apparently, Williams never did settle down with his family but he evidently played and toured in Europe and notably The Netherlands for stretches of time in the early 1980s. He also was part of the Mingus Dynasty tribute band.

Williams passed away in 1985 in New York City.