Red alert.

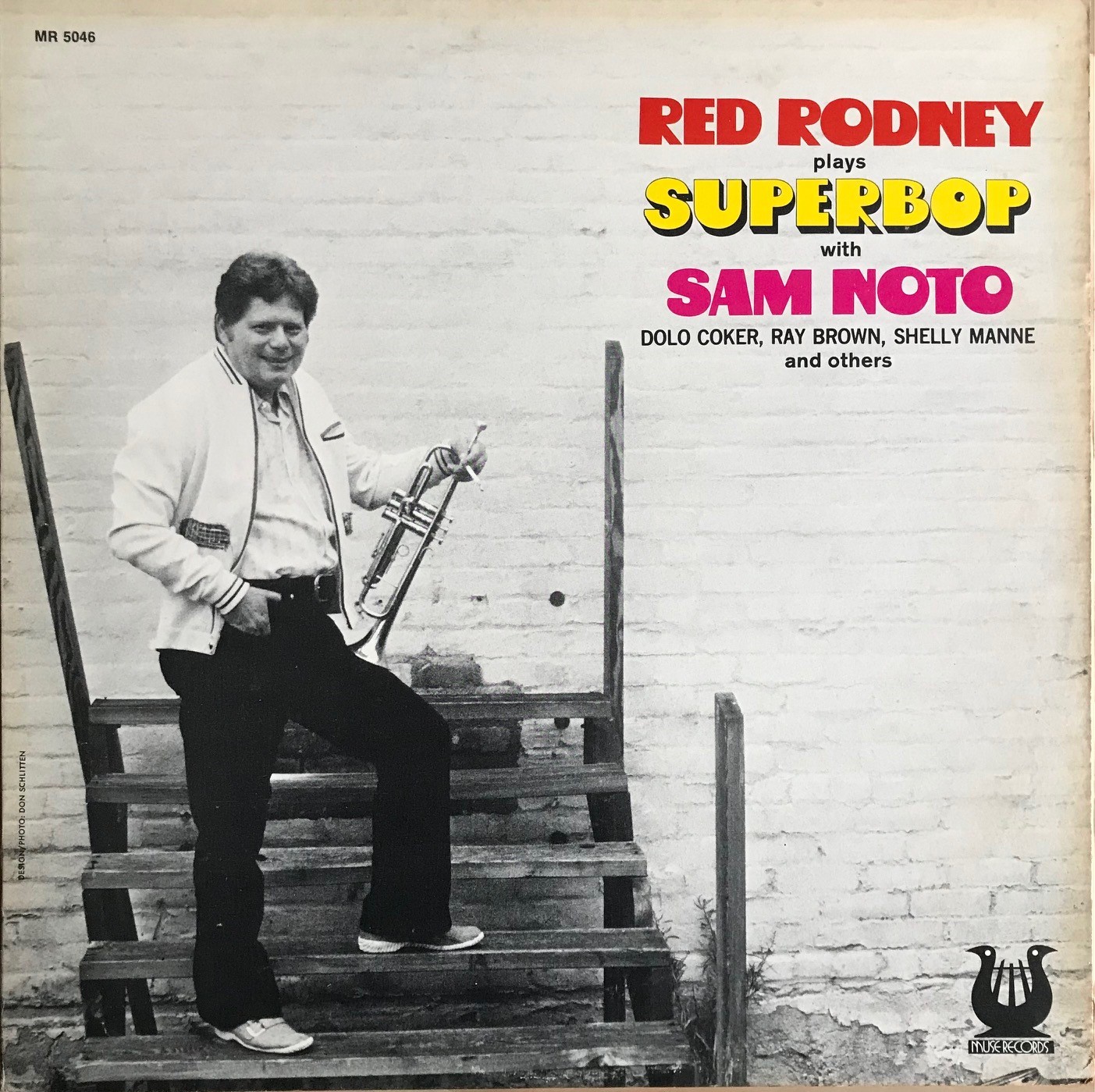

Personnel

Red Rodney (trumpet), Sam Noto (trumpet, flugelhorn), Jimmy Mulidore (alto saxophone, soprano saxophone, alto flute), Dolo Coker (piano), Ray Brown (bass), Shelly Mann (drums)

Recorded

at Wally Heider Recording Studio in Los Angeles

Released

as MR 5046

Track listing

Side A:

Superbop

The Look Of Love

The Last Train Out

Side B:

Fire

Green Dolphin Street

Hilton

The crook or the outlaw does everything that you and I don’t dear dream of. He roams the country with a bunch of thieves and gypsies. Beats up a guy that throws plastic baskets from McDonalds out the window of his SUV on the freeway. He’s down and out and sleeps off hangovers on the beach. Understanding everything and nothing at the same time, he’s liable to brooding between stretches of high action. It’s what you would call ADHD nowadays, but in his world, the realm of Attila the Hun and Mickey Spillane, ADHD is just another painkiller on the market.

His whole life is a statement about the illusion of freedom. He’s hard as a brick except when it comes to animals. He lives by his wits and the sorrow of the world hangs on his lapels as backpacks on the coat racks in school. His life is a crust of blood on the forehead. Honor is his middle name. To the point of madness. He sometimes travels with his stepson. He says he’s the happiest man on earth and that’s the one thing that bothers his stepson’s mother. What bothers hím is that the further away he is from reality, the better he understands it.

Red Rodney knew all this. He lived a life that transcends the absurd. It is a life story that is well-known by the serious jazz fan, written down unforgettably by Gene Lees in his seminal book Cats Of Any Colors. Born Robert Roland Chudnick in Philadelphia in 1927, Rodney played in the bands of Jimmy Dorsey and Benny Goodman before breaking through in the band of Charlie Parker. It was all bebop from that point on. As the only white member of the group, Rodney was billed as “Albino Red” during stints below the Mason Dixie line. Unfortunately, he also committed himself to the lifestyle of Bird and became a heavy user of heroin and assorted substances.

(Red Rodney; Charlie Parker & Red Rodney watching Dizzy play; Sam Noto, Rodney’s frontline partner on Superbop)Beboppers were the cultural outlaws of the 1940’s. Often derided by conservative colleagues or critics, their music was not only an extreme jazz evolution, it also reflected the signs of the times, its seemingly frenzied but highly complex and structured sounds in sync with war and post-war upheaval and the acceleration of developments in American society. They were the underdog, people that were rock & roll before the term existed, people that, to paraphrase an evergreen, ‘couldn’t go home again’ although the one that formalized it, Dizzy Gillespie, ultimately was a dedicated family guy.

Rodney was far from home. Luckily, the trumpeter succeeded to survive while other boppers like Dick Twartzik, Serge Chaloff and Sonny Clark fatally overdosed, but after his long and successful stint with Parker, Rodney gradually dropped out of sight. He made a couple of records in the late 1950’s but generally took to theft to sustain his habits. Rodney immersed himself in swindling and fraudulent activities and took no half measures. At the height of his crookdom, Rodney conned various insurance companies for major sums of money and impersonated as a doctor in order to obtain and sell prescriptions. Grand schemes, as if the crew from Ocean Twelve was united in one person.

Rodney’s most outlandish adventure in the 1960’s was his impersonation as a USA Army general and robbing money and secret documents from the vault of an army base. It was only a matter of time before Rodney got caught, no matter how ingenious his games of hide and seek with the law. Rodney served several jail sentences, although his uncommonly special rapport with prison managers and other servants of the law stood him in good stead. Often, the disadvantaged institutions didn’t care for the publicity and confined to deals with the red-headed stranger. Note that the ‘gentle crook’ eschewed from robbing his fellow man/woman but instead focused on the anonymous establishment.

Rodney spent years in the pit bands in Las Vegas, while his teeth were in horrible condition, and this looked like the end of his jazz career, until he met a fine lady in the late 1970’s in New York City. She cleaned him up and Rodney obtained new dentures, enjoying a highly unexpected, minor comeback, functioning as an older and wiser mentor to many young lions and recording frequently until his death of cancer in 1994.

He apparently was in bad shape in the 1970’s. So, it’s quite surprising that Rodney did manage to make a couple of excellent records. His first album in 14 years in 1974, Bird Lives, was fine though had its share of weaker moments, but the follow-up from the same year, Superbop, was flawless from start to finish. Hi-octane, to boot. It coupled Rodney with fellow trumpeter Sam Noto, saxophonist Jimmy Mulidore, pianist Dolo Coker and the heavyweight rhythm section of bassist Ray Brown and drummer Shelly Manne.

Of course, it would be hard to find a weak session when Ray Brown is aboard, giant of the double bass and the Big Boss Mann of the studio. So, that might be one of the main reasons that Superbop worked out so well. Rodney and Noto work together on the sparkling ensembles as Siamese twins and hunt each other in the choruses as foxes and rabbits. Interestingly, Noto is the first soloist on five of six tunes, which reveals the generosity of the veteran to the underrated Kenton and Basie-ite. This is fish in a barrel for Brown and Manne. Brown particularly, and typically, is a forceful presence, now and then walking in duet with Rodney, and providing great suspense to boot.

Superbop, a line that’s derived from the solo by Clifford Brown from Daahoud, thrives on the vitality of Rodney and Noto’s trumpet stylings. The vibe of Burt Bacharach’s The Look Of Love, featuring muted Rodney, is pleasantly reminiscent of Miles Davis. Dolo Coker seizes his Bud Powell-ish opportunity on the fast-pased Last Train Out, a Sam Noto tune. Rodney and Noto’s Fire is a rapidly expanding forest fire and it’s a line that reminds of Salt Peanuts. Plenty salty but predominantly oozing with the sharpness of chili pepper. The Latin-tinged treatment of Green Dolphin Street is no slouch either.

This is superbop indeed, fusion and synths and odd meter be damned. Though the modal mid-tempo Hilton, written by Mulidor, points out that Rodney was not stuck in rigid traditionalism. He’s just doing what he does best, thrivin’ on an unbeatable and rather riveting riff.

Listen to Superbop on YouTube here.