Sonny Stitt suffered from the constant comparison with his friend Charlie Parker. Fact is, former manager of Ray Brown, Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven explains, that The Lone Wolf, contrary to common belief, already played bebop before he’d ever met Bird. A long-awaited debunking of myth.

You read about the nomads in North-Africa in history books. Or see them on tv on Discovery Channel. Weather-beaten people with leathery, wrinkled, red faces, dressed in full desert regalia, long robes from neck to feet, ingenuously arranged turbans on their heads. They’re wobbling on camels from dune to dune, finally reaching a tiny bit of half-fertile land, settling for a while, then moving on to the next challenge. Minding their own business. Until somebody takes them away as slaves. Or hires them as a tourist attraction below union scale.

The similarity with jazz legends is striking. You read about them in history books as well or, if you’re lucky, see them on public tv in a documentary, most likely on the European broadcasting systems. Somebody might give you a tip to go see the Miles Davis documentary on Netflix, featuring various fellow legends as supporting roles. This is the only way to know about them because, for various reasons, one being that America still hasn’t come to terms with the implications of an indigenous art form that simply by being itself defied white supremacy, the history of jazz is still largely absent from the curriculum of the educational system in the USA. (Let alone the history of serious rap and hip-hop, which was partly fueled by jazz and the most extreme – extremist – Afro-American outing in the history of American musical culture, essentially completely alien to WASP teachers, parents and kids and dealing with matters too scary to touch.)

In Hollywood, jazz is a tourist trap. To date, the jazz artist hasn’t been depicted on the big corporate screen in the manner he or she genuinely moves or behaves. Not even once. (Bird? Well… with all due respect: no) The latest effort was the jazz part of Babylon. Not quite. Unless professional jazz musicians are featured, e.g. Jerry Weldon and Joe Farnsworth in Motherless Brooklyn, these efforts are fruitless. (Not counting the indispensable European indie flick Round Midnight with Dexter Gordon)

So far, so bad. If poverty of portrayal is omnipresent, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that education falls short.

The jazz legends lived a truly nomadic life. Though they rarely if ever traveled with family. Jimmy Forrest worked on the riverboat in the band of the enigmatic Fate Marable. Up and down the Missouri and the Mississippi rivers time and again. Arnett Cobb journeyed with the so-called territory bands in the Mid-West, dust everywhere, in his nose, ears, crotch, brain. Duke Ellington worked around the clock, somewhere, somehow. He sat beneath Harry Carney in the car and traveled more miles on the American highways than Boeing 747’s fly over the oceans in their life span.

Charlie Parker, The Bird. Quite the wanderer in his all-too short and turbulent life. Sonny Stitt, The Lone Wolf. He liked to travel alone from East to West and North to South, picking up local rhythm sections and hard cash.

Speaking of Bird and The Lone Wolf. Whom crossed paths occasionally in their lives. Famously the first time, in 1942. Do you remember that story? Good one. Great jazz lore. Initially, it was chronicled by former promotor Bob Reisner in his book Bird: The Legend Of Charlie Parker in 1962. The story was quickly adopted by Ira Gitler for his liner notes of Stitt’s 1963 album Stitt Plays Bird. And repeated by critics and fans to this day.

However, Reisner and the herd forgot to mention or were ignorant of one thing. To be precise, nothing less than the punchline.

Early in his career, when he was 19 years old, Stitt played in the band of singer and pianist Tiny Bradshaw. Stitt had heard the records that Charlie Parker had done with Jay McShann and was anxious to meet him. Finally, one day, the band reached Kansas City, Bird’s place of birth. (see picture of Kansas City’s club-filled black district around Twelfth Street during the era of political boss Tom Pendergast below) Stitt: “I rushed to Eighteenth and Vine, and there, coming out of a drugstore, was a man carrying an alto, wearing a blue overcoat with six white buttons and dark glasses. I rushed over and said belligerently: ‘Are you Charlie Parker?’ He said he was and invited me right then and there to go and jam with him at a place called Chauncey Owenman’s. We played for an hour, till the owner came in, and then Bird signaled me with a little flurry of notes to cease so no words would ensue. He said: ‘You sure sound like me.’”

That’s it. That’s the official story. But it ends prematurely.

Because Stitt retorted: “No, yóu sound like me!”

“Yeah!” says Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven. “It’s amazing that none of the people in the business cared to tell the real story.”

(Stitt; Bird; Twelfth Street, Kansas City)

Swiss-born Jean-Michel Reisser was nicknamed “Beethoven” by the legendary Harry “Sweets” Edison. Son of a serious record collector that befriended jazz legends in the 1970’s, Jean-Michel sat on the lap of ‘uncle’ Count Basie as a three-year old kid. He eventually befriended Basie, Ray Brown, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Max Roach, Jimmy Woode, Milt Hinton, Sonny Stitt, Dizzy Gillespie, Hank Jones, Jimmy Rowles, Alvin Queen and various others. A savvy cat, he was hired as manager by Ray Brown. Besides managing Brown, Jean-Michel produced hundreds of records, tours and jazz documentaries. He has retired from the business now, lives in luscious Lausanne and, as passionate about his beloved art form as he’s ever been, is an enlightening jazz causeur.

“I would be stupid not to overwhelm all those legends with questions while they were still living and breathing. That way, I heard a lot of stories, directly from the source.”

Sonny Stitt, though, was rather reticent. “He was a great guy, but didn’t talk much. You had to take him by the arms and say, ‘hey motherfucker, I have some questions! He was the kind of guy that liked to drink and smoke and relax after a concert. It was only privately that Sonny ultimately got down to conversating about music.”

The punchline raises multiple issues. About the ignorance of the press. (Though Gitler, as we’ll see, spitballs something interesting at the issue.) About the mystery of parallel inventions in art. And, not least, about Stitt’s reputation and life. Much to his dismay, Stitt had to deal with comparisons with Charlie Parker all his life. Small wonder, since Stitt has always been a straight-ahead bop saxophonist, variating, apart from various commercial records, largely on the prevalent Tin Pan Alley changes and bebop’s contrafact compositions. However, a mere cursory afternoon of comparative listening between Stitt and Parker will reveal largely differing personalities to all listeners that trust their ears, whether beginners or aficionados.

Stitt’s a thoroughbred. Fine horse, plenty bulging muscle, shiny brown manes. Charging out of the gate, running powerfully but smoothly, eye on the finish line. Goal-oriented.

Bird’s a pinball at the mercy of a pinball wizard. It is eloquently maneuvered on the plate. Then, with a sudden push, it is smashed through the glass, careening around the arcade and miraculously jumping back into the machine.

No, yóu sound just like me!

Come again?

Reisser-Beethoven: “That’s the truth. It’s what Sonny told me when we talked about his meeting with Parker. Significantly, many people have told me about their interaction with Sonny. First of all, Ray Brown. Ray met Sonny in 1943. Ray said that he hadn’t heard about Parker until a bit later. He said, ‘I heard this young guy playing things I never heard before. Everybody says he’s playing like Bird, I said, no way. Sonny always had his own style’. Hank Jones played with Stitt in 1943 and he told me the same story. J.J. Johnson as well. He said he’d never heard about Bird until 1944, but he’d already played with Sonny Stitt: “This motherfucker had his style. He didn’t play like Parker. He played in the same vein, but it was different.’ Stan Levey told me a similar story.”

Vein is the word here.

Reisser-Beethoven continues: “This is the way of the arts. You sometimes see it happening in painting, that two great painters arrive at a similar concept. It works this way in music as well. For instance, the late Benny Golson explained to me that he composed a lot of tunes that he thought were pure originals but found out by listening to the radio that others had reached the same conclusion, without ever hearing Benny’s drafts. As far as the story about Stitt and Parker goes, Parker hadn’t totally arrived at his original style when he played with Jay McShann. It was only in 1944 when he had fully developed bebop harmonics. Stitt arrived on the scene a bit later and in the public eye and everybody said that he played like Parker. But historically, this is not the case.”

It is the way of the arts but also extends to other areas. Politics and social history, for instance, with strings of misunderstanding attached. Take Martin Luther King’s iconic I Have A Dream speech. Contrary to general belief, King didn’t invent the groundbreaking oneliner. He’d heard Prathia Hall, daughter of Reverend Hall, utter those words in a remembrance service in church after an assassination on black citizens. King used the sentence in subsequent speeches but it didn’t catch on until he so imposingly integrated it in his speech at the march to Washington, urged by singer Mahalia Jackson.

Back to our musical icons. Paradoxically, Reisner and Gitler mention an occurrence that backs up the idea that giants like Parker and Stitt arrived at the same musical conclusions apart from each other. (In this respect, it should also be noted that drummer Kenny Clarke worked on new rhythms in the very early 1940’s, a glimpse of the congruency of ideas of Parker, Gillespie, Clarke, Roach, Monk, Pettiford, Mingus, Powell in the mid-1940’s) Reportedly, Miles Davis saw Stitt coming through St. Louis (Davis’s birthplace) in 1942 with Tiny Bradshaw’s band, ‘sounding much like he does today as far as general style is concerned’. Gitler says: ‘We don’t know whether this was before or after the Kansas City confrontation, but Stitt has long insisted that he was playing this way before he heard Parker.’

Chockfull of lore, Gitler’s liner notes of Stitt Plays Bird (by the way, a record with some stellar solos by Stitt, regardless of the underwhelming band spirit) also mentions something that Charlie Parker supposedly said to Stitt a little while before his death in 1955: ‘Man, I’m not long for this life. You carry on. I’m leaving you the key to the kingdom.’

Epic. Lord Of The Rings-style. However, nobody in his right mind believes Bird to be capable of uttering such pompous near-last words. ‘Please pass that piece of lobster,’ seems more likely. Or, in a more serious friend-to-friend/father-to-son vein, ‘I urge you not to do as I did, stay away from the needle’.

In fact, Bird did say something of the sort to young disciples, that didn’t listen and with few exceptions got hooked. Nothing of the sort was advised to Sonny Stitt, though, who lived with his own demons and did time in Lexington, Kentucky in 1947/48. Precisely at the time that bebop gained nation-wide traction. Bad luck. Reisser-Beethoven: “I’m sure that his being out of the public eye was a setback, but his main problem was criticism. He suffered from big depressions throughout his career. Everybody presented him as a clone of Charlie Parker. It was problematic. He wanted to quit many times. Eventually, he alternated with tenor saxophone. Dizzy Gillespie came up with this idea in 1946, when Sonny was in Dizzy’s band. Suddenly nobody said anything about Bird! Although he played the same lines, chords, improvisations. Dizzy said to me that, when Parker didn’t show up, he’d either call Lucky Thompson or Sonny Stitt. He loved Sonny Stitt.”

“In his view, Norman Granz saved his career. Granz took him out on the Jazz At The Philharmonic tours. He recorded him with Dizzy, Sonny Rollins and produced all those Verve albums. Sonny considered his Verve albums as the highlight of his career; notably Sits In With The Oscar Peterson Trio, New York Jazz, Plays Arrangements From The Pen Of Quincy Jones. He also believed his albums in the early 1970’s with Barry Harris, Tune Up, Constellation and 12! to be among his best.”

And so, the nomads traveled from East to West, North to South, dark-skinned birds and lone wolfs roaming from one asphalt jungle another, sometimes jubilant, rejoicing notes brimming with blues and Debussy, as excited as kids on a funny farm, sometimes shivering, hiding in a torn raincoat, at the end of the rope and the track. Charlie Parker and Sonny Stitt crossed paths more than once. Reisser-Beethoven: “Allegedly, they met several times. As far as I’ve heard, they were good friends. Charlie Parker didn’t say anything bad about Sonny’s style, no way. Dizzy said that sooner or later the critics were bound to put walls between them. It’s not only like that in music. But also in politics, religion, history. All too often, one guy tells the so-called definitive story and the rest follows it blindly. It’s a pity.”

Sonny Stitt

Here’s Stitt Plays Bird: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0I2Lcnn_hLs

Here’s I Remember Bird: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gMEpRUTE_no&list=OLAK5uy_nuKI1RZPqZVIsRMGYW7kGI9RNO1uuxoRs&index=2

The Happy Blues

From sitting at the feet of her grandmother and the turntable as a toddler in Osaka to jazz mecca New York and the international stage, organist Akiko Tsuraga has come a long way, still thriving on the inspiration from mentors Lou Donaldson and Dr. Lonnie Smith. “I’m trying to do as they did as much as I can, which is playing for the people first and foremost.”

She keeps staring into space. At a point beside the screen where, it seems, a dehydrated spatula has fainted while walking to the faucet on the kitchen counter. Then she simply says: “I miss him so.”Tsuraga refers to alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson, who passed away on November 9, 2024, at the venerable age of 98. She was part of Donaldson’s organ group for many years, heir to a line of illustrious forerunners that includes Lonnie Smith, Baby Face Willette, Big John Patton, Charles Earland and Leon Spencer.

A while later, while discussing her entrance in the New York scene in 2001 – troubled and tragic times in American history – Tsuraga falls silent again. When she has regained her posture, she explains that, without denying how horrible the WTC disaster was, she already knew all about tragedy, referring to the horrendous earthquake in Kobe, Japan in 1995.

Humble Tsuraga goes for content instead of verbosity, ‘less is more’ instead of waterfalls of words. No mistaking, she offers plenty expression and often exhibits her typical laughing mood, laced with delicate twists of consent, puzzlement, unease and enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is the mood that she carries to the stage, where she oozes joy and where her notes laugh like kids in the playground and smile like grandparents sitting at the curb of the sandbox. The Osaka-born organist is a fixture on the New York scene, collaborating frequently with stalwarts as saxophonists Jerry Weldon and Nick Hempton, guitarist Ed Cherry and, not least, her husband, ace trumpeter Joe Magnarelli. Tsuraga released seven albums as a leader on various labels. Her latest is Beyond Nostalgia on Steeplechase. She doesn’t rest on her laurels and recorded a new album with drummer Jeff Hamilton, to be released in 2025. In May, Tsuraga hits the studio in Vancouver for a recording with the Vancouver Jazz Orchestra, a future Cellar Music release.

New York City remains home base, the Bay Ridge area in South Brooklyn to be precise. Her unlikely journey from Osaka to the jazz heart of The Big Apple is a curious mixture of talent, perseverance and pivotal encounters with the cream of the classic jazz crop. “Before I went to New York, I was working in clubs in Osaka. I used to play at an after-hours-club across the street from the Blue Note Osaka club. Many musicians who played there stopped by after their gigs. The after-hours-club had a Hammond B3 organ. I met so many people and had a chance to play with Grady Tate, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Brother Jack McDuff, Jeff “Tain” Watts, Kenny Kirkland, Joey DeFrancesco, Larry Goldings, Earl Klugh.”

She continues: “I was already very good friends with my mentor (drummer, FM) Grady Tate in Osaka. When I started out in New York, he helped me out a lot, showed me around places and introduced me to people. Dr. Lonnie Smith helped me in similar ways. I’d met him through drummer and mentor Fukushi Tainaka, who also introduced me to Lou Donaldson. I went to the Showman organ club in Harlem every week and met Jerry Weldon for the first time. Eventually, the club gave me a gig. When Dr. Lonnie left Lou’s group (After Smith’s tenure with Donaldson’s group in the mid-1960’s, he reconnected with him for many years the 1990/00’s, FM), Dr. Lonnie and Fukushi recommended me. Lou came to the Showman and after the first set he said, ‘Ah, Akiko, you’re so brave! Coming to New York by yourself! And you sound better than any male organist around New York.’ Lou said that I needed to learn how to comp behind horn players and that he was going to teach me. We played all over the world, long tours in Europe, Japan and on American festivals. It was an unforgettable experience.”

A far cry from her youth in Osaka. Though, that’s disregarding the Japanese fascination with Western/American culture in the 20th century, regardless of world wars. Tsuraga: “My grandmother was a big jazz fan. I heard many jazz records that way. And I loved the sound of the organ. My parents bought me a Yamaha organ when I was three years old. I started taking piano lessons as a kid and studied at Yamaha Music School. I got the chance to play all sorts of music there, American popular music, jazz, fusion.”

Plenty reason for nostalgia. But Tsuraga, as her latest album reveals, rather looks beyond nostalgia, without forgetting the richly layered roots of organ jazz. Beyond Nostalgia is an unabashed variation of organ themes. Sassy swinging modern jazz originals like Tiger alternate with the old-timey reenactment of Mack The Knife. The souped-up What A Difference A Day Makes is counteracted by the relaxed shuffle of The Happy Blues, which precedes the modal album highlight, Middle Of Somewhere, conceived after an ice-fishing trip with a friend in Wisconsin. The title track is a lovely mood piece. What’s the story behind Beyond Nostalgia? “I wrote that song after I visited the temple in Kyoto. I went with my sister. It’s a very spiritual place. It was such a beautiful experience, we were crying. Birds were humming and suddenly that melody came to me. The temple is the birthplace of ‘reiki’, hand-healing.”

Tsuraga has been involved with reiki for a long time. “I love it. Since I followed classes, I started to realize that when I play organ, my fingers feel much stronger and more sensitive. I love that feeling. You know, Dr. Lonnie Smith had really powerful hands. He would unintentionally break Iphones and Ipads! A friend of mine who works at Apple says that people with exceptionally strong hands sometimes break those screens. I was thinking, if I have the same power, my playing will improve and be just like Dr. Lonnie’s!”

She tells it with one of her enticing variations of laughs, part apologetic, part matter-of-factly packaged see-what-I-mean. It’s easy to see what she means with her final remark, though it must be said that by now her playing is nothing less than Tsuraga’s.

Akiko Tsuraga

Check out the website of Akiko and her discography here: https://www.akikojazz.com/

Find Beyond Nostalgia on certain questionable streaming platforms and buy here: https://propermusic.com/products/akikotsuruga-beyondnostalgia?srsltid=AfmBOorPIlRfkJg11PhWiXg9g46V_UJTY51Wsevzpl7lcGaBlvLlWiLT

Picture header: Joseph Berg.

Picture 1-3: Lou Donaldson & Akiko; Akiko & Lonnie Smith; Akiko & Jerry Weldon

He stepped out of a dream

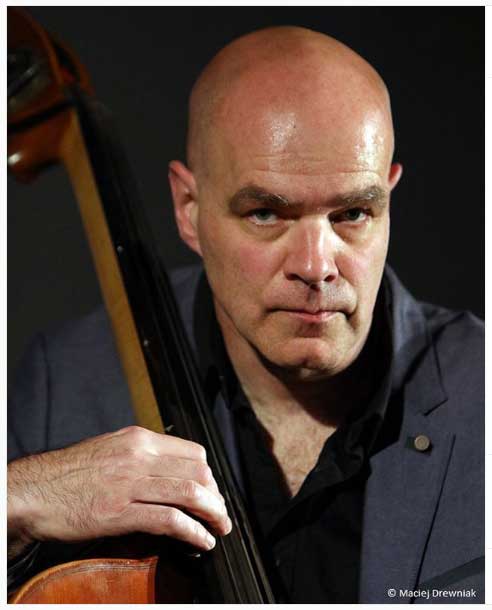

Sought-after bassist Joris Teepe has been on a very tight schedule for decades, a Holland-born New York stalwart with an imposing career as leader, sideman and composer. One of various latest projects is The American Dream Today. Teepe’s personal good fortune contrasts sharply with worrisome socio-political developments. “It seems like everybody continues to live as if everything will eventually turn out fine. But I wouldn’t be too sure about that.”

He’s a tall, solid man, the kind you don’t accidentally want to bump into in the crosswalk. Regardless of his solid frame, Teepe suddenly found himself falling to the ground just recently, dazed and confused. On stage, to boot, at the Blue Note club in Athens, Greece. “I suddenly felt awful, sweating profusely. Danny (Grissett, FM) saw that I was collapsing and the guys rushed over. I had to go to the hospital. It turned out that I had a bacterial infection. Unfortunately, we had to cancel the last two shows.”Teepe is charging his batteries at his home in Amsterdam, a cup of tea in front of him. His wife is out, his son is at school. At his large kitchen table, Teepe casually goes through some of his recent activities, his unassuming manners differing strikingly from the impressive nature of his list. His itinerary included promotional gigs of Steve Nelson/Joris Teepe/Eric Ineke’s Common Language album, the release of saxophonist Johannes Enders’ The Creator Has A Master Plan B and his umpteenth recording with his soul mate, saxophonist and flutist Don Braden, At Pizza Express Live In London. Teepe recently recorded with Polish trumpeter Piotr Wojtasik and will make his debut on Steeplechase in January on Mythology by drummer Steve Johns. He’s playing with young piano wizard Theo Hill and continues to perform with piano maestro Rob van Bavel as Dutch Connection, not least on the upcoming North Sea Jazz Festival. Finally, Teepe released his Joris Teepe Real Book, a collection of 96 Teepe compositions and a rare feat.

A busy bee, right from the start in the early 1990’s, when Teepe burned some bridges and settled in New York City. He made fast friends and colleagues and never looked back, the only Dutchman in history, amazingly, that permanently made his mark in The Big Apple. Teepe’s career includes shows and recordings with luminaries as Chris Potter, Cyrus Chestnut, Jeff “Tain” Watts, Randy Brecker, Billy Hart, Tom Harrell, Lawrence Clark, Lewis Porter, Tim Armacost, Jeremy Pelt, Gene Jackson and many others. He regularly toured with Benny Golson. From 2000 till 2009, Teepe was bassist in the band of Rashied Ali, Coltrane’s last drummer.

Living the dream, so to speak. That’s partly why he titled his latest record The American Dream Today. “When I grew up as a musician in The Netherlands, I saw all those crazy and top-rate American cats in Europe. I desperately wanted to be part of that crew. Eventually, I succeeded to become a part of the scene in New York, which was and to my mind still is the jazz mecca. I’m glad I persevered because I wouldn’t have been able to experience and feel the history of jazz in The Netherlands as you do in the USA, with all due respect. Besides, obviously, over there you get a crash course in taking care of business.”

Teepe continues, referring to revealing titles as Polarization, Fake News, My Car Is Bigger Than Yours, The One Percent and Today’s Dream: “But there’s more to it. That’s why I added ‘Today’. I’m an American citizen because I also have an American passport. What is happening since Trumpism, and today, what with the re-election of Trump, is very troubling. The classic American Dream of having a big house, a family, two cars, both preferably bigger than those of your neighbors, may have been regarded as a bit silly, but it’s far better than what is happening today. Polarization and fake news are very dangerous developments. Trump’s climate denial is disastrous. The Western Gaza-policy is horrible. I’m more politically conscious than I used to be. As an artist, you’re in a unique position, having a stage figuratively speaking but also quite literally, with a microphone in your hand. Admittedly, I’m preaching to the choir, but it’s better than nothing. Maybe someone after a concert might be inspired and become a member of Amnesty International, little things like that are worthwhile.”

The American Dream Today, which offers solution with the lively Music Is The Answer, is as varied as a wild veggie patch, full of shiny strawberries, heavy zucchinis, fresh parsley, intense ginger. It includes Marc Mommaas on saxes, Adam Kolker on saxes and woodwinds, Ian Cleaver on trumpet and flugelhorn, Leo Genovese on piano and Fender Rhodes and Matt Wilson on drums. Teepe’s band at his recent live tour, which mixes Dream with other songs from the Teepe book and was seen by Flophouse at the Bimhuis in Amsterdam, consisted of Ian Cleaver, Don Braden, trombonist Luis Bonilla, pianist Danny Grissett and drummer Gene Jackson. (This band minus the lamented Jim Rotondi was the logical choice after a performance with the Noord-Nederlands Orkest) Both bands make the most of Teepe’s strong repertoire, which links uproar with melancholy, jubilance with a sense of foreboding and is marked by a striking tension between composition and freedom. How did the prolific tunesmith arrive at his method? “There is before and after Rashied Ali. I have always written compositions, basically in the mainstream. Meeting Rashied changed everything. It was not only unforgettable to work with someone who had such a close connection with Coltrane and had such great stories of that era, but a life-changing period for me as a musician and writer. He had a very different way of thinking about music and composing. For Rashied, it didn’t matter if everything fell into AABA and 4 bars. He just said, well, about one minute of this is okay… For him it wasn’t about the rules but about the feeling, about how people would react and a deeper level than just the technical side. It was so exceptional because it didn’t come out of the blue. Rashied knew all the songs from Broadway. He used to hum and sing those tunes all the time back in the van. He had grown up with those tunes but wanted to transform those tunes into something else.”

Teepe professes an admiration for the writing of Wynton Marsalis, notably Black Codes (From The Underground) and Vince Mendoza and Bill Holman, both of whom Teepe worked with in orchestral projects. Teepe is also artistic advisor and teacher at the Prins Claus Conservatory in Groningen and brought countless American friends and colleagues over to The Netherlands for workshops and performances. He’s been traveling between his apartment in New York and his home in The Netherlands for many years. How long is the 62-year-old bassist going to keep up this relentless commuting? “I feel like a New Yorker, even if I’m here a lot of the time. I met my wife when I was living in New York twenty years ago. She lived there for some years, though she prefers Amsterdam. So, what can I say! It takes two to tango. My son is 14 and would love to live in New York. At any rate, I live the biggest part of my jazz life over there. When I walk into a club, everybody knows who I am. It’s not like that over here. I remember touring with Benny Golson. We played in the Bimhuis. So, Benny introduced me, saying something like, ‘on bass, it’s your homeboy… Joris Teepe. Well, three fourth of the audience didn’t know who I was.” Teepe laughs: “It’s twenty years ago. I’m a bit better known these days in The Netherlands, because I have been more active. I’ve found a nice balance of shuffling between New York and The Netherlands.”

Does his son play an instrument? Teepe, matter-of-factly: “He started out on piano, then switched to bass. He’s a great bass player. He’s a fast learner and grooves like mad. You may catch him playing Jaco Pastorius stuff from the top of his head, it’s crazy. But he doesn’t like to practice. It seems that he wants to quit. Obviously, he’s in puberty, so there you go. I’ve never put any pressure on him, it’s his own choice. He thinks twice because he sees the amount of traveling that I need to do. And all those old people sitting in the audience.”

Joris Teepe

Check out the website of Joris and his discography here: https://www.joristeepe.com/

Find The American Dream Today on Planet Arts here: https://www.planetarts.org/the-american-dream-today1.html

Ricardo Me

Portuguese guitarist Ricardo Pinheiro is all about melody and tone and meanwhile making up musical stories with a who’s who from Europe, USA and Brazil. “I’m working with my idols, so I’m very happy.”

Pinheiro shows the view from his house with his camera. A big garden, rows of trees of multiple heights at the edge. A crystal-clear blue sky. It’s Sintra, a short drive from Lisbon. The gorgeous Sintra Woods and Mountains were a retreat for Portuguese nobility, full of opulent castles and villas. The forests are dense like giant wombs, the hills are jagged like gigantic rock elbows and various locations offer a breathtaking view of the ocean nearby. To say the least, living in Sintra is not a punishment. “It’s beautiful. I grew up in Lisbon, but I came to Sintra when I was 17. My parents built a house. I lived here for three years before I went to study at Berklee in Boston. When I got married, me and my wife were wondering where to live. Prices in Lisbon were high. Not as crazy high as nowadays, but higher than Sintra. We got an apartment and then, after the birth of our second child, moved into this house.”The beauty and splendid serenity of Sintra inspired Caruma, Pinheiro’s refined and moving piece of guitar and voices featuring singers Theo Bleckmann and Monica Salmasso from 2020. Clearly, Pinheiro can’t be confined to a small space. He got plenty heads turning as a sidekick to Dave Liebman and never looked back, releasing various, singular albums of standards, straight-ahead and prog jazz, acoustic and Brazilian-Portuguese flavored songs, free improv, jazz and poetry and cinematic scores. A kid in the candy store of guitar music. “There wasn’t an instrument in the house until I asked for a guitar at age 14. I was soon playing heavy metal. Metallica and Iron Maiden. I was in a band that even recorded in the UK. But when I was about 17, I felt the need to study theory. That meant playing jazz at the Hot Club Jazz. My grandfather listened to Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Broadway tunes, Brazilian music. It was old people’s music to me then. It was okay, but old! Still, I started to get into standards, learning harmony. Then I got into John Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson. Charlie Parker. Slowly but surely I started understanding it and loving it.”

You could do worse than, a couple decades later, assembling a line-up of saxophonist Chris Cheek, bassist Michael Formanek and drummer Jorge Rossy. They are part of Pinheiro’s newest Fresh Sound Records release, Tone Stories. A set of standards that includes well-known warhorses as When You Wish Upon A Star and Blame It On My Youth and seldom-played hard bop classics as Elmo Hope’s De-Dah and Dexter Gordon’s Fried Bananas, marked by the angular yet lyrical playing of Pinheiro, embedded in the colorful sounds of the all-star cast. It’s a warm and smoothly flowing album, apple pie fresh out of the oven. And nothing tastes quite as good as his version of Jimmy Rowles’s seminal ballad The Peacocks, achingly beautiful from start to finish. “Tone is the quality of sound. I like to think of the album as a set of stories that are told with the tones of each player, which together make the sound of the band. And we’re telling a story with each song. Chris and Michael have incredible tones. Jorge as well. He had definite ideas of how he wanted his drums to sound, especially during the ballads. He said to the engineers, ‘I’m not playing like a typical drummer, behind everything, chink chink… Please put me up forward in the mix. I’m painting sounds.’ Jorge is one of my favorite drummers of all-time, period. So, this album is a dream come true.”

From heavy metal, the tradition of Wes Montgomery to the invigorating input of the school of the 90’s. Pinheiro enthusiastically reflects on the influence of his postmodernist elders. “I belong to the first generation that was inspired by people like Jorge Rossy, Brad Meldhau, Mark Turner, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Chris Cheek. They incorporated a lot of tradition but with a new flavor, used the same tools in a different way. It’s not Wes but also isn’t fusion. When Meldhau did those pop songs, it really connected with me. Jazz can be like this, wow. It wasn’t playing pop as pop, but pop like jazz. Brad, Jorge and Chris redefined things, formed new musical proposals. Nobody played even eights like Jorge. Nobody had the timbre of Kurt or the two-handed independence and the classical vibe of Brad. Or played the upper part of the horn like Mark. Their groups joined two worlds, tradition and fusion, together in a peaceful way. They deserve all the credit.”

He sometimes starts solos where you least expect it. Paves the way to a resolution with quirkily melodious twists and turns. Pinheiro’s style is a refreshing mixture of asymmetry and lyricism. He doesn’t restrict himself to the vintage 1950’s aesthetic. On the contrary. He allows himself the odd display of effects and volume and tone control, with extraordinary results. During The Peacocks, his handling of volume control mingles like a human voice with Cheek’s suave soprano. Back in 2017, he made When You Wish Upon A Star into a psychedelic tour de force, almost as if he was playing in The Grateful Dead or Iron Butterfly or Pink Floyd or was playing along with the thirteenth take of The Beatles’s Tomorrow Never Knows, with Massimo Cavalli and Eric Ineke on Triplicity. The same trio repeated the uncanny feat on their 2022 version of Bill Evans’s Time Remembered. And effects and tone control are all over Caruma or 2013’s Tone Of A Pitch. Pinheiro stresses an important fact: “Melody is all-important. I’m not thinking about hip runs or large intervals. If music has no melody, there’s no point in my opinion. But I like different things. I’m like a chameleon. Tone aesthetic comes with the history of jazz, in a way. The classic guitarists were thinking about their tone. Way back, I started listening to John Scofield and Bill Frisell and started experimenting with delay, overdrive and reverb to color the music. But I avoid exaggerating at all costs, I don’t want to obscure the message and the melody. I envision sounds and try to go for it, either with thinking about strings, how to use my hands or with effects. The incredible Ben Monder has been very important to me. He taught me how to use effects and tone control without confusing things up. It took a few years of experimenting.”

Pinheiro hooked up with various class acts through the years. He met Dave Liebman and Dutch drummer Eric Ineke through the International Association of Schools of Jazz, which was founded by Liebman. His albums were released on Greg Osby’s Inner Circle label and Jordi Pujol’s acclaimed Fresh Sound Records, among others. A well-connected gent. “Fresh Sound was one of my favorite labels. I fell in love with those records from Meldhau and Rosenwinkel. I kept in touch with Jordi ever since the release of my debut album Open Letter in 2010. It’s kind of my nature to take matters in my own hands. I’m a little… how shall I say this, not ashamed.” Pinheiro laughs. “I harass people! That’s how I got in touch with Chris Cheek. Back then, I knew Chris was coming to play here. He had done four albums on Fresh Sound and I thought they were absolutely fantastic. I sent him an email and asked if he wanted to record and he agreed. I asked if he could talk with Jordi. He happily obliged and that is how my first album Open Letter came about. Now we’ve got Tone Stories and another one in the can already with the same quartet.”

Neatly trimmed coupe, healthy tan, bright eyes, rapid, enthusiastic flow of speech. One easily understands why colleagues, apart from his original musicianship of course, like to work with the resident of Sintra and jazz teacher. He’s eager to continue his striking partnership with Massimo Cavalli and Eric Ineke. “We’ve got another album coming up, we’ve finished recording just last month. Massimo and I have a great understanding. And I love to play with Eric. He’s one of the most swinging drummers out there, so easy to play with. Energetic, yet sensitive. There’s no effort, strain, doubt, he always is totally aware of the structure of the music. He carries with him this big history of playing with loads of giants of jazz.”

Among other endeavors, notably working with Grammy-winning Brazilian singer Luciana Souza and having the exceptional improvisational skills of Portuguese Maria João on a soon-to-released solo album, Pinheiro is currently striking up a cooperation with none other than famous Brazilian composer and singer Ivan Lins. “I contacted him and sent some songs. He said that they were beautiful and suggested that he write lyrics. I couldn’t believe it. I’m over the moon.”

Swinging The Melody

Parisian bass player Cédric Caillaud has very original and specific ideas about how to expand on the tradition. “There are plenty ways of creating new things in the standard repertoire.”

He will be back in New York next week. More than two decades ago, Caillaud, as ambitious young lions are wont, started to check out the Big Apple scene. Now he’s reached the age of forty-eight and takes along his teenage daughter for the trip down memory lane and a ride through the bowels of the asphalt jungle. “It’ll mostly be big fun and sight-seeing. But I will visit friends and go and see music at places like Small’s. I had a band with pianist Spike Wilner at one time. As the owner of Small’s, he is doing a great job for jazz.”Regardless of his transatlantic connections and though Caillaud tours quite a bit in Europe, even as far as West-Africa, the La Rochelle-born bassist is firmly based in Paris. One of the most gorgeous places in the world, City of Light, City of Romance and for jazz buffs, forever linked with unsurpassed American expatriates as Kenny Clarke and Bud Powell, Paris is a place that has always had jazz running through its veins. At any given night, lone half note rangers and flocks of paradiddle-doers enter the premises of one of the beautific ‘arrondissements’, instrument case in hand, in the case of Caillaud, a big bag that holds his upright bass. He’s a staple of Chez Papa in St. Germain du Près and Le Petit Opportune nearby Les Halles.

A sought-after player that played and recorded with a variety of people from Scott Hamilton, Bobby Durham, René Urtreger to Manu Dibango, Natalie Dessay and Thomas Dutronc, Caillaud recorded four albums as a leader. A far cry from his beginnings in La Rochelle. “It is impossible in this region to be a professional musician. La Rochelle is a quiet and nice provincial town. But I was interested in music and started playing electric bass in the weekend. Your typical garagerock. Me and my friends loved the Jimi Hendrix Experience. I discovered Jaco Pastorius and Weather Report. That’s how I basically got into jazz. At that time, I didn’t know who they were. I thought that they were a bunch of young guys! It was only later that I learned that Wayne Shorter was a famous jazz musician and that Joe Zawinul had played in the Cannonball Adderley Quintet. I started going to the mediatheque and borrowing real jazz records. That’s when I changed to double bass.”

Caillaud is a strong bass player with a sound like a big woman that wears stockings and high-heeled boots made for walking. A tone that rattles the bottles behind the bar. A worthy contender in the lineage of Ray Brown, John Clayton, Pierre Boussaguet, he strives for a challenging combination of groove and confident intermezzi. “Essentially, I’m proposing another role of the bass. The evolution of double bass in popular music is very significant. It is a genuine solo instrument by now. Why not play melodies and solo’s? I love to let people discover the beauty of the double bass.”

Moreover, Caillaud makes it his business to carefully arrange all his projects, giving every of his four albums a distinct vibe and challenging allocation of roles whether it’s the hard-swinging Emma’s Groove or the lithe and airy With Respect To Jobim. “I want everything to have a live feeling, to give people music that lives and breathes. In order to achieve this, I use original arrangements and stress different colorings. That’s why on, for instance, the Jobim record, I featured flutist Hervé Mischenet. He’s a genuine flute player, not a saxophonist that plays flute on the side. And he used four different flutes to realize the coloring that I was looking for.”

Swinging The Count, featuring pianist Patrick Cabon and drummer Alvin Queen, serves as a top-notch, rather stunning example. Why this tribute to Count Basie? “Basie is a very important sound. Most people talk about Duke Ellington. And I love Duke Ellington. I play the Ellington book in the Duke Orchestra in France, a great orchestra. But Basie is about the essence. He didn’t read, played blues and gave a special feeling of happiness and exuberance. He played music from other composers but gave it his own identity. It’s pure swing. I have a lot of experience playing the Basie repertoire in great groups like drummer François Laudet’s big band. On Swinging The Count, it was a very great experience to play with the amazing Alvin Queen. He has a real black beat. My goal was to celebrate Count Basie’s music in trio form. That has never been done with this line-up. Oscar Peterson did quartet recordings and there’s the two Count Basie records with Ray Brown and Louie Bellson. I love the Basie recordings from the 1950’s and 1960’s because of the maturity of Basie and the sound of the bands. Amazing quality and great composers and arrangers like Quincy Jones and Neal Hefti.”

He’s the kind with good faith in mainstream jazz. “It’s perfectly possible to create new things in the mainstream repertoire. Essentially, jazz is very simple. It’s like Alvin Queen told me: ‘It’s just swing and melody!’ Of course, you can have different inspirations like African or Asian music or whatever and create a lot of things. But basically it’s all about context. I love someone like Benny Green. Each recording is always musical, lively and in the tradition.”

The generation of Caillaud, inspired by the resurgence of interest in classic jazz, music that had balls and grew from the earth like potatoes and cucumber and chili pepper, was embraced by the old guard. “It was important to me to play with older musicians and listen to their stories. I was friends with Pierre Michelot. He told me: ‘When I was young, I started to play with older musicians, I learned the repertoire and I learned to play. Then I became a veteran. But it was impossible to play with the young people in the 1980’s. They didn’t know the repertoire and only played their own compositions.’ It was frustrating for him to deal with the fusion period. But he was happy when my generation arrived.”

And now Caillaud spreads the word to inspiring youngsters around town. Lucky little boogers!

Cédric Caillaud

Discography:

- June 26 (Aphrodite 2006)

- Emma’s Groove (Aphrodite 2009)

- Swinging The Count (Fresh Sound Records 2013)

- With Respect To Jobim (Fresh Sound Records 2020)

Check out Cédric and his albums on Fresh Sound here.

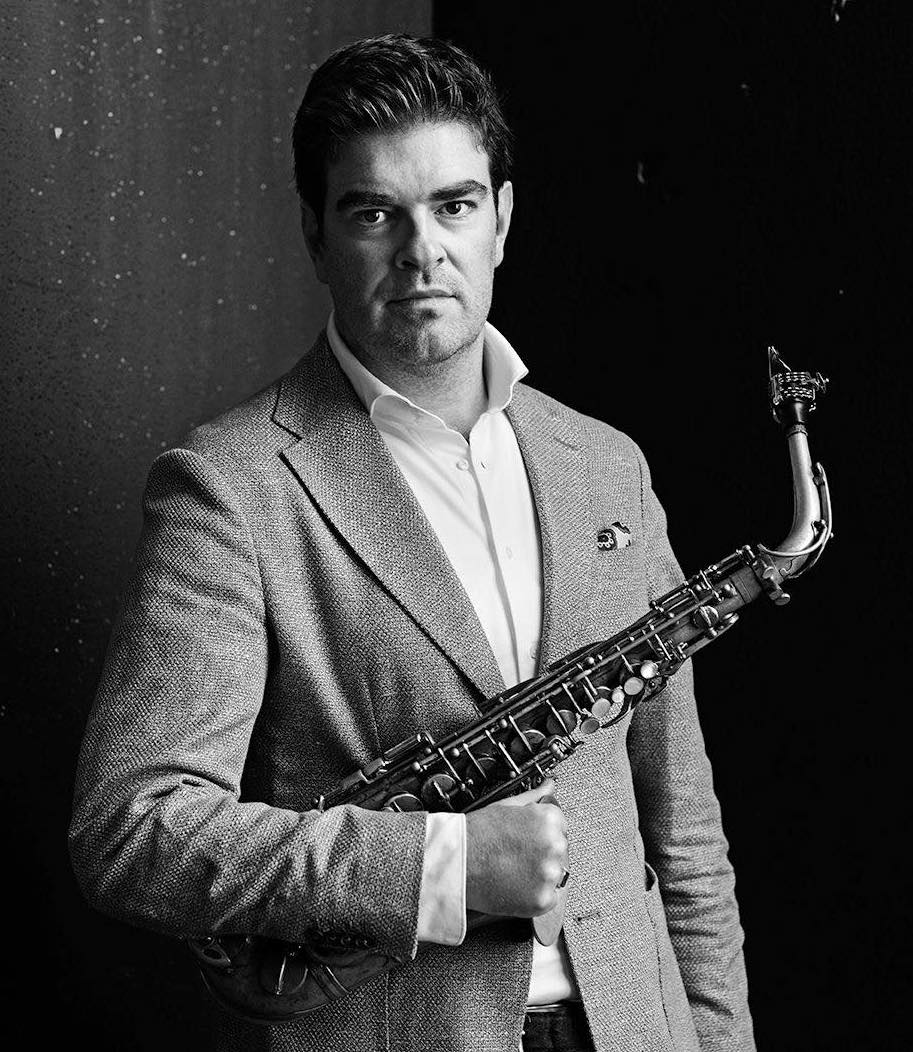

Zing went the strings of his heart

Lyrical alto saxophonist and canny jazz entrepreneur Tom van der Zaal thought big and cooked up an album with strings. “It’s taken three good years of my life. I wanted everything to be top-notch.”

Bright blue, yellow and red rays of light dart across a stage that almost resembles Madison Square Garden. Pools of sweat bring back memories of the last monsoon season. Crazy young fans dominate the clean scene. Van der Zaal shows pics of his performances at various Indonesian jazz stages. He grins excitedly. “I’m a bit jetlagged. It’s quite a trip and the difference between climates is enormous. But it was all worth it. It is like playing at a pop festival and the people keep you in high regard. Most of the fans over there are young and absolutely crazy. But not merely crazy in the sense of plain enthusiasm. Some of them knew all about my work and said that they had been waiting for my visit for years. It’s fantastic. The tour was cancelled a few times. But it finally came through with the support of the Erasmushuis.”He hovers over an espresso at Jazz Coffee & Wines on the beautiful Noordeinde street in The Hague. Quite the opposite of Jakarta. A gusty wind comes down from the North Sea. Its residential grandeur warms your bones. The city that seats the national government is the home base of Van der Zaal, a well-groomed, vivacious fellow with a healthy blush on his cheeks. Bon vivant. Go-getter. Having arrived at the second phase of his career, not a young lion anymore, Van der Zaal is out there to compete and cook up new strategies. He’s serious about the definition of ‘new’ and gains traction after his well-received Time Will Tell album from 2019, which featured ace guitarist Peter Bernstein.

His next ‘phase’ involves Sketchbook Of Dreams, which adds a couple of rearrangements of compositions from Time Will Tell to new material that was specifically written for this inspired ‘with strings’ project. “A lot of ideas come up at night. It seems that creativity is inspired by darkness. When I get an idea at night, I get up out of bed and write it down or sing a melody in my phone, even if it’s only four bars. It may be a starting point for something to work on the coming day. They’re like sketches.”

An all-consuming affair. One doesn’t put together a string album overnight. Van der Zaal is much akin to a quarterback that takes up the extra tasks of coach, agent and personal trainer. “This kind of project usually involves a team of approximately eight people. I’ve almost done everything myself. Preparation, arranging, budgeting. I’m quite ambitious and don’t care whether it takes sixteen hours a day. It turned out to be a very good occupation for me during the pandemic. It kept me busy and in fine mental health. And I knew that I had some good thing going on once the restrictions were abandoned. At least, after all this work a good response is what I’m hoping for!”

“It basically comes down to an expansion of all kinds of capabilities. Both business-wise and artistically. Musically, it has been quite challenging. Writing charts and arranging is not something that you just do on the side. I really dug into the practice day and night. Obviously, I’m familiar with the great ‘with strings’ records of Charlie Parker, Clifford Brown, Frank Sinatra. But I wanted to make my own kind of album. I listened a lot to the treatments of classical pieces by Bill Evans and threw myself into the string quartets of Ravel and Mahler. I am very much influenced by their movements and intervals.”

“Even still, I’ve got a lot to learn and look forward to work more often in this vein in the future. It really fits my style like a glove. I’m a lyrical saxophonist and match well with the warmth of strings. 50% of what I do is sound, so I really need to take care of it! That’s why I’m also a gear geek. I ordered one of those famous Ribbon microphones that amplified the tone of guys like Cannonball Adderley. But it got stuck at customs. I had to use another mic. It’s probably undiscernible but things like this keep bothering me. Still, it turned out beautifully.”

You oughta take Sketchbook Of Dreams to your second date. You won’t take no for an answer. Put it on. The flickering of candle flames heightens the intensity of melancholia. The streetlights wink languorously to the lamp post. The piano is tipsy, telling corny jokes. It’s a lush affair, to say the least. Bordeaux wine-red strings embrace the tender but punchy alto saxophone of Van der Zaal. The palette ranges from Coltrane-ish drama to sweet-tart balladry. The great Dutch pianist Rob van Bavel accompanies beautifully and embellishes the intriguing movements of Dance Of Hope And Prospect. Van der Zaal rebounds from his chair. “Rob is a giant. Every time I hear him play I keep thinking that Holland is blessed to have a guy like this in its ranks. We specifically wrote Dance Of Hope And Prospect for Rob.

A subtle Latin feel is predominant throughout the album. “Our bassist Matthias Nicolaiewski is Brazilian. I keep asking him for new music, the things that almost nobody is familiar with out here in the West. That’s how we came up with Luiza from the legendary Antônio Jobim, one of his lesser-known tunes. It’s one of the most beautiful melodies ever and suits the range of the alto sax perfectly.”

Van der Zaal hired the Grammy Award-winning engineer Dave Darlington to look at the scores. He specifically wrote string introductions so that he may switch between performances with quintet or orchestra and tease audiences with radio edits on Spotify. He considers a vinyl release and is planning performances in Brazil, Indonesia, the illustrious Ronnie Scott’s in London. A man with a plan. “There’s an idea behind all aspects of the album. In general, I have reached the age that I don’t need to make miles any more like a youngster playing for a couple of bucks in bars. I do enjoy playing, of course, but I’m more conscious of what I’d like to achieve.”

He has come a long way from the boy that grew up in the home of a saxophone-playing father, who passed on his musical genes and business acumen. “I grew up with a strong sense of the tradition and listened to Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges, Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke. My father had a job but he played alto saxophone and clarinet. He has great ears and intuition. I have been lucky, because he took me to rehearsals and concerts when I was just a little kid. I studied with Simon Rigter and David Lukasz when I was 16. Around that time I went to my first afterparty at North Sea Jazz, taken by the sleeve by Wynton Marsalis, soaking everything up until 10 in the morning. That was when the jazz bug really got to me.”

North Sea Jazz has moved to Rotterdam. The jazz life of The Hague is close to his heart. For four years now, Van der Zaal and singer-songwriter Toine Scholten have organized the Jazz En Route festival, performances in various places along The Hague’s elegant avenues. “It’s mainstream but we look for a connection with postmodern stuff. We’re not aiming for a new North Sea Jazz. But I have noticed that there is a certain nostalgic feeling among musicians, certainly Americans. They miss that special vibe. Jesse Davis said that one of our places gave him that old North Sea feeling for the first time in twenty-five years. He was talking about our spot at the Indigo Hotel. You wander through a kind of speakeasy bar, then a cocktail bar, until you’re in a great jazz room. It’s a really cool experience.”

Van der Zaal washes away his last espresso with a small glass of water. He smiles, tired but fulfilled. “Once the sound of the last notes has died from the December festival, the organization for next year starts. It is a very time-consuming affair. It’s somewhat like Sketchbook Of Dreams. ‘All or nothing at all’, so to speak.”

Tom van der Zaal

Check out Tom’s website here.

King Queen pt. 2

Here’s part 2 for you and yours, Alvin Queen talking about his stint with Horace Silver, the European continent of opportunities, the way the legends nudged him to change his style of drumming and the way jazz was and will never be again if something isn’t done about it very soon. “I don’t play any music that the people can’t figure out. They paid and have first priority.”

Temperature is rising and there ain’t no place to go. Beet-red heads nod off in the subway train. Someone put our crotches in the oven. It’s the kind of sticky heat that leads to perennial complaints from the Dutch tribe. Alvin Queen flew over from Geneva to The Netherlands, Rotterdam to be exact. He’s here for the North Sea Jazz Festival and a performance with trumpeter and bandleader Charles Tolliver and the Rotterdam Youth Orchestra. His schedule reads like the itinerary of a foreign minister who is visiting a much-anticipated climate conference and wastes two pairs of shoes in a period of 36 hours. The soles of Mr. Queen’s footwear, not to mention his sticks and brushes, have to endure a lot. There isn’t any time to be wasted. Plane, hotel, rehearsal, hotel, soundcheck, performance, hotel and… plane.Rehearsal with a capital R. It is scheduled from 2 to 9, which surpasses the 10 to 4 at the Five Spot extravaganzas of the classic era of jazz. An imaginary octet of jazz courts jesters overheard his remark that ‘I never heard of no rehearsal of seven hours’ and add an extra hour of Rehearsal. Tough luck. The immaculate professional takes it in stride. If anything, it’s a jazz family affair. A gift from King Queen to Prince Charles. “I usually don’t play in big bands. I’m not a good reader and have never really liked it. There is no opportunity to be a creative artist. I prefer the spontaneity of small ensembles.”

Alvin Queen is 74 years old, by no means an old-timer but an elder statesman beyond doubt. He’s the same age as some former fusion artists, who also wear the officious label of veterans, but comes from a totally different jazz planet. When fusion and electric jazz reigned supreme in the early 1970’s, Queen, student of mentor Elvin Jones, participant in the gospel scene of Scepter Records and the black organ jazz club circuit, drummer of the Horace Silver and George Benson bands, changed his course. Queen regularly toured in Europe with Charles Tolliver’s original installment of Music Incorporation and rejoined Horace Silver’s quintet. The continent of new opportunities continued to beckon and after a two-year stay in Montréal and many gigs in Europe, Queen settled permanently in Geneva, Switzerland in 1979, “Baby Queen” to the touring elder statesmen of jazz such as Ray Brown, Clark Terry, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis and Milt Jackson. The halcyon days.

FM: When you were playing with Horace Silver again in the early and mid-1970’s, what was the repertoire?

AQ: “When you make a hit record, that’s what people want to hear. I was sick of Song Of My Father! Horace said that we had to play it and we sometimes played it two or three times a night. That was the way it went. Miles had to play So What, Coltrane My Favorite Things and Cannonball Adderley Mercy Mercy Mercy by Joe Zawinul. We also played Sēnor Blues and Filthy McNasty. But then Horace changed up and started going into spirituality and recorded the United State Of Mind records. One night I said, ‘Horace, all that Hare Krishna stuff, God, what is going on?’ He said, ‘Alvin, I haven’t changed my music, it’s just the lyrics’.”

FM: I heard a story that while you were with Horace Silver, you also took care of business for Stan Kenton. Something to do with loose women.

AQ: “That’s right. We were playing the Jazz Showcase in Chicago around the time of In Pursuit Of The Seventh Man. We were staying in the Merlin hotel. Kenton was in the hotel and he had a whole lotta money in his hands. Whores were standing around and keeping an eye on him. I said, ‘Stan, come on, man, put the money away.’ I took him up, put him to bed, kept the money in envelopes. I left him a message to call me in the morning. It was right in time before they would stick him up, haha!”

FM: It tells me you were on the ball and dependable, two things you also need as a drummer.

AQ: That’s right. Apart from swing.

FM: You played a lot in Europe in the 1970’s and eventually settled there permanently in 1979. Why did you decide to go and live in Europe and why Geneva?

AQ: “Well, the American scene was electrified, the music had changed, you had big acts like Weather Report. I had a taste in the early seventies with Charles Tolliver and Stanley Cowell. I met my future wife in Geneva at a party and that is how I managed to stay there eventually. The location was perfect. I could go to France and Germany. I was in the center of things. Important guys like Francy Boland and Pierre Michelot asked for my services. Europe was good to me.”

“I worked with Duke’s bassist, Jimmy Woode in 1972. It’s a funny story. When I was twelve years old, I recorded in New York City. They hired Joe Newman as musical director and he hired Zoot Sims, Hank Jones and Art Davis. Harold Mabern substituted for Hank. I was 12! It was never released. So, when I came to Europe, Jimmy and Joe were arguing about me, Joe saying, ‘I did his record!’. From my association with Jimmy Woode, I ended up with the older generation of musicians, you see. Harry “Sweets” Edison, Clark Terry, Dolo Coker, Lockjaw Davis. At that time, all Count Basie’s men came as individuals to do gigs. A very important thing for me was that I became the house drummer of the festival in Nice in the South of France. You had Oliver Jackson, Gus Johnson, Panama Francis and me. Sometimes, you know, one of them got boozed up and drunk, that was fine because I would play two sets a day and get even more money that way! I played with people like Marian McPartland, Wild Bill Davis, Guy Lafitte, Michel Goudry, George Arvanitas, Michel Saraby and Pierre Boussaguet. I played all over France from then on.”

(Jimmy Woode & Harry “Sweets” Edison, Nice 1980s; Ray Brown & Milt Jackson; Charles Tolliver)FM: A lot of the greats that you played with at that time, Milt Jackson, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Ray Brown, Dexter Gordon, they played with Charlie Parker. Did they talk about Charlie Parker?

AQ: “They always talked about Parker at the dinner table and such. It was between Parker and Billie Holiday. Later on, when I played with Oscar Peterson, he would talk about Billie Holiday all the time.”

FM: How did you got involved with the great Ray Brown?

AQ: He heard a lot about me long before we came into contact, about 15 years before that. Everybody was talkin’, Ray knew about me and he said, ‘Queen, I’m gonna get you someday!’ That was the way it went those days. So, I came to Europe and needed work. Jimmy Woode spread the news, ‘I saw this kid, he can play…’ Ray and I would bypass each other all the time. I was playing with Milt Jackson and John Clayton at the time. John also talked with Ray. So, when Ray did his 70th Birthday Party in Paris with Roy Hargrove, Art Farmer, Jacky Terrason and Pierre Boussaguet, Ray said, ‘Come on, Queen, only time we got a chance, let’s do this…’ We established a fine relationship. Ray was playing a lot in Zürich back then.”

FM: Speaking of Milt Jackson. You always hear that he didn’t enjoy playing in the Modern Jazz Quartet and that he wanted to get out there and swinging. Do you think that’s true?

AQ: “The Modern Jazz Quartet was a conservative group and John Lewis was a very classical type of person. The group was created company-wise, there was equal share for each musician and it was one of the most exclusive, highly-paid bands. The thing is, they did the Carnegie Hall, tuxedo and bow tie kind of thing but went to places áfter the gig to jam. Connie Kay went to Jimmy Ryan’s a lot. He played with guys like Major Holley and Roy Eldridge. Milt said to me, ‘I can make John Lewis swing, man!’ But if you heard Milt with the MJQ, he sounds different than with Ray Brown and Monty Alexander at Shelly’s Manne-Hole. (That’s The Way It Is and Just The Way It Had To Be – Impulse 1969/70, FM) I played with Milt and Sadik Hakim in Montréal at the time of his Olinga album. I knew where he came from and he was swinging. Anyway, we all did that, jamming after the gig, Coltrane, Stan Getz, everybody.”

FM: You also went to Africa in the early 1970’s. how did that come about and what you did do out there?

AQ: “That was something that came about through the National Endowment of the Arts. Randy Weston and Nina Simone signed up for me in support. I did performances and workshops in ten countries, from Ghana, Gabon, Burkina Faso and Cameroun to Benin, Togo and Zaire. Every African country had embassies in the USA and I played at the residencies of ambassadors in Africa.”

FM: Your album Ashanti is very African in nature. It’s one of your finest records. What was the idea behind that record?

AQ: Well, after we did the music in the studio, I got the idea of doing a drum battle. I played against each track and so, with two drummers going on, we got this special vibe. The name had nothing to do with the Ashanti people. My wife had an old custom mask that she had gotten many years ago in Africa on the marketplace. It’s not an Ashanti mask, by the way. But the first thing I said when we had recorded the album and I saw the mask was, ‘ashanti’. That record was very successful.”

FM: It was released on your record label Nilva. Why did you start your record label?

AQ: I started Nilva because no one was producing me. I made so much money in Europe, I didn’t know what to do with it. I had never made that kind of money. I watched what Charles Tolliver did with Strata-East. I had a radio tape and produced my own record. (Alvin Queen in Europe, FM) Then a friend told me, if you got an ice cream company, you gotta have all flavors… So I went to New York and did the Ashanti record. It took off and I did those records with Dusko Goykovich, Junior Mance. John Hicks was on most of the stuff. I was very close with John Hicks. I produced Ray Drummond’s record with Branford Marsalis.” (Susanita, 1984, FM)

FM: Why did you quit eventually?

AQ: “The business changed. I was a one-man operation. It was impossible for me to put all that stuff on CD.”

FM: As a drummer, you encapsulate both Elvin Jones-inspired playing and straight swing, it’s very interesting to hear.

AQ: “I was there with Tony Williams at the time. I saw the change from time keeping to free playing. I watched Elvin Jones and Roy Haynes, who had started that thing with Sarah Vaughan. He was low in the mix but you could hear it, the triplet style. Tony and Ron Carter played double with Miles. All drummers followed these guys. Later on, in Europe, the older guys would tell me, stop dropping them bombs… We couldn’t play free like that. It was tempo first. All drummers followed Tony and Elvin but no one turned back to Denzil Best or Shadow Wilson or J.C. Heard. But you need them tóo. There’s no background to a lot of players today, you see. If you say, let’s play the blues, they collapse. I’d be glad to teach them! If you pay respect, I’ll help you out.”

FM: You can’t do without the lessons from the elders.

AQ: “I sat around listening to all those stories from Ray Brown and Oscar Peterson. That already is one thing how you learn to play, that’s by keeping your ears open. These guys teach you how to be solid, not to move around. It’s good to play with all these different personalities. Nowadays, it’s technique. The time is weaker than the technique. That’s the problem.”

FM: Perhaps there should be more of those, but I do know young players here in Holland who soak up everything local and international old masters do and have to say 24/7. That’s the spirit.

AQ: “That’s good but the school and industrial system remains problematic. Bandleaders are not supported. The real masters are not supported. I’ve never been supported and I know a lot, you see? What I have to give don’t make money. What they’re giving us is a market of people that aren’t masters yet. In the history of jazz, all new leaders came out of working groups. They came from the bands of Coleman Hawkins, Max Roach, Art Blakey and not from school. I had no problem getting along with the older musicians because I had that type of training at home. Respect your elders. I was in the bands of Harry “Sweets” Edison, Arnett Cobb, Jay McShann, Buddy Tate. If you were with the elders, you stayed out of the conversation. You didn’t have that experience, so it was best to be quiet and learn.”

“Most professional teachers are not real bandstand players. They teach you the notes but not the experience of the bandstand. I tell younger musicians, who you wanna copy? Who you wanna be? I wanted to be Art Blakey, Elvin Jones. I found a sound for myself. I was in the bands of Horace Silver, George Braith, Larry Young. They said, ‘don’t do this, do that, pay attention, take the grime out of your ears, put your mind to it, use the brain, not the notes.’ That’s how I learned. We don’t have that connection between bands and new leaders and that’s a serious problem. Education is great but it’s totally different than the bandstand. I played with everybody on earth. I gave mine but I just watch where things could improve.”

(AQ, Oscar Peterson & Dave Young, North Sea Jazz Festival, 2005; photography Evert-Jan Hielema)FM: In your definition, the last generation of masters probably is the one that came up in the 1990’s. You played with a lot of those, the Marsalis brothers, Nicholas Payton. Roy Hargrove.

AQ: “Roy Hargrove only played his gigs when he came in and sat in with granddaddies that were lightyears older than him. I was playing a gig with Dado Moroni and Walter Booker and young Roy was sitting on the side of the steps. He hit me in the leg, ‘hey, Mr. Queen, can I sit in?’. ‘Yeah man,’ I said, ‘that’s where the microphone is right there.’ I loved Roy Hargrove. He admired the elders and loved to play with them. He wanted to know where it was at before it was too late. His experience is sadly missed in New York. He had an every-night jam session going on, man.”

FM: So, we don’t have to expect to have any new young masters?

AQ: “Not if we don’t have bands and leaders, we won’t. A master is a guy who can hold a beautiful tone which blends in with everything. In the Basie band, all trumpeters went into a room and each held one note, so it would sound like one. The ‘one note school.’ I used to sit real close and watch the group of Thelonious Monk. I would hear the gut string of the bass. Wilbur Ware would play one note, no amplification, and it went like, BOOM. The bottles rattled behind the bar. They’re masters. One of the problems today is that 90 % of the musicians move around and don’t stay sturdy.”

FM: Are you going to release some new stuff in the near future?

AQ: “I’m working on a new record right now. It has Tommy Morimoto on saxophone. He’s been running around for twenty years but nobody ever gave him a break. Carlton Holmes is on piano and Danton Boller on bass. He was with Roy Hargrove. I met him through Benny Wallace. I don’t want any people with names. I don’t want four bandleaders on stage, there’s gonna be conflict. I’d rather be the only one there.”

“It will feature four-or-five minute tunes like The Night Has A Thousand Eyes and It Ain’t Necessarily So. I want people to listen to the radio and think, wow, where has that song been? The trick in music is to keep it simple. Let it happen, don’t try to make it happen. If your grow, the music is a part of you. With life, you grow. Music is like food. If you’re a chef in the kitchen, the food tastes better years from now than it does at the present because you learn how to cook the food right.”

“I paid my dues, I have a right to make a statement. I never said I was a mentor because I never reach my goal. When I die, I still haven’t reached it. I just go to another dimension. If I reach my goal, there’s no reason to create anymore. Too many people think that they are already there. That’s when you’re blocking your goal. I went to Oscar Peterson and asked him one time, ‘tell me something, how does it feel to be a genius?’ He said, ‘come into the room and shut the door and sit down!’ He said: ‘Look, people say I’m a genius. But I’m an ordinary piano player like you are an ordinary drummer.’ Great wisdom. And when I die, I die with the basics, with the wisdom.”

Alvin Queen

Quotes:

Harry “Sweets” Edison: “Alvin reminds me of the original drummers that I worked with in the 30’s and 40’s. He has it all. I have to play at 150% of my capacity. If not, he’ll put me out of stage. Alvin keeps me young every note I play with him. He’s fantastic.”

Clark Terry: “Alvin is one of the most swinging drummers of all time that I know and have played with.”

Ray Brown: “Alvin is not only one of the top drummers for sure but also one of the most swinging and crazy guys that I know.”

Frank Wess: There’s only one Alvin Queen in the jazz world. Period!”

Kenny Drew: “If Alvin leaves the trio, I’ll never hire another drummer.”

Selected Discography:

As a leader:

In Europe (Nilva 1980)

Ashanti (Nilva 1981)

Lenox & Seventh (with Lonnie Smith – Black & Blue 1985)

I’m Back (Nilva 1992)

Nishville (Moju 1998)

Hear Me Drummin’ To Ya! (Jazzette 2000)

This Is Uncle Al (with Jesper Thilo – Music Mecca 2001)

I Ain’t Looking At You (Justin Time 2005)

O.P. (Stunt 2018)

Night Train To Copenhagen (Stunt 2021)

As a sideman:

Charles Tolliver, Impact (Strata-East 1975)

Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Jaw’s Blues (Enja 1981)

John Patton, Soul Connection (Nilva 1983)

Guy Lafitte/Wild Bill Davis, Three Men On A Beat (Black & Blue 1983)

Pharaoh Sanders, A Prayer Before Dawn (Evidence 1987)

Tete Montoliu, Barcelona Meeting (Fresh Sound 1988)

Kenny Drew Trio, Standard Request: Live At Keystone Corner (Alfa 1991)

George Coleman, At Yoshi’s (Evidence 1992)

Pierre Boussaguet, Trio Charme (EmArcy 1998)

Cedric Caillaud Trio, Swinging The Count (Fresh Sound 2012)

Check out Alvin’s website here.