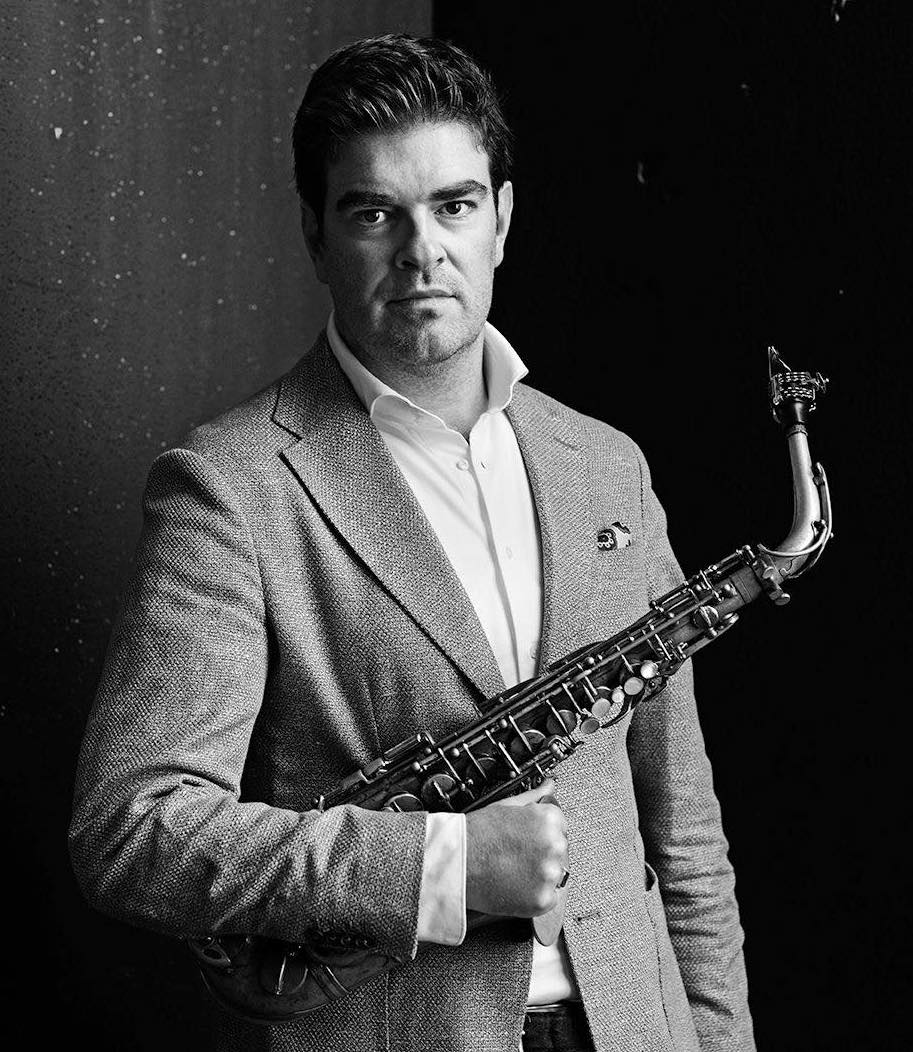

Parisian bass player Cédric Caillaud has very original and specific ideas about how to expand on the tradition. “There are plenty ways of creating new things in the standard repertoire.”

He will be back in New York next week. More than two decades ago, Caillaud, as ambitious young lions are wont, started to check out the Big Apple scene. Now he’s reached the age of forty-eight and takes along his teenage daughter for the trip down memory lane and a ride through the bowels of the asphalt jungle. “It’ll mostly be big fun and sight-seeing. But I will visit friends and go and see music at places like Small’s. I had a band with pianist Spike Wilner at one time. As the owner of Small’s, he is doing a great job for jazz.”Regardless of his transatlantic connections and though Caillaud tours quite a bit in Europe, even as far as West-Africa, the La Rochelle-born bassist is firmly based in Paris. One of the most gorgeous places in the world, City of Light, City of Romance and for jazz buffs, forever linked with unsurpassed American expatriates as Kenny Clarke and Bud Powell, Paris is a place that has always had jazz running through its veins. At any given night, lone half note rangers and flocks of paradiddle-doers enter the premises of one of the beautific ‘arrondissements’, instrument case in hand, in the case of Caillaud, a big bag that holds his upright bass. He’s a staple of Chez Papa in St. Germain du Près and Le Petit Opportune nearby Les Halles.

A sought-after player that played and recorded with a variety of people from Scott Hamilton, Bobby Durham, René Urtreger to Manu Dibango, Natalie Dessay and Thomas Dutronc, Caillaud recorded four albums as a leader. A far cry from his beginnings in La Rochelle. “It is impossible in this region to be a professional musician. La Rochelle is a quiet and nice provincial town. But I was interested in music and started playing electric bass in the weekend. Your typical garagerock. Me and my friends loved the Jimi Hendrix Experience. I discovered Jaco Pastorius and Weather Report. That’s how I basically got into jazz. At that time, I didn’t know who they were. I thought that they were a bunch of young guys! It was only later that I learned that Wayne Shorter was a famous jazz musician and that Joe Zawinul had played in the Cannonball Adderley Quintet. I started going to the mediatheque and borrowing real jazz records. That’s when I changed to double bass.”

Caillaud is a strong bass player with a sound like a big woman that wears stockings and high-heeled boots made for walking. A tone that rattles the bottles behind the bar. A worthy contender in the lineage of Ray Brown, John Clayton, Pierre Boussaguet, he strives for a challenging combination of groove and confident intermezzi. “Essentially, I’m proposing another role of the bass. The evolution of double bass in popular music is very significant. It is a genuine solo instrument by now. Why not play melodies and solo’s? I love to let people discover the beauty of the double bass.”

Moreover, Caillaud makes it his business to carefully arrange all his projects, giving every of his four albums a distinct vibe and challenging allocation of roles whether it’s the hard-swinging Emma’s Groove or the lithe and airy With Respect To Jobim. “I want everything to have a live feeling, to give people music that lives and breathes. In order to achieve this, I use original arrangements and stress different colorings. That’s why on, for instance, the Jobim record, I featured flutist Hervé Mischenet. He’s a genuine flute player, not a saxophonist that plays flute on the side. And he used four different flutes to realize the coloring that I was looking for.”

Swinging The Count, featuring pianist Patrick Cabon and drummer Alvin Queen, serves as a top-notch, rather stunning example. Why this tribute to Count Basie? “Basie is a very important sound. Most people talk about Duke Ellington. And I love Duke Ellington. I play the Ellington book in the Duke Orchestra in France, a great orchestra. But Basie is about the essence. He didn’t read, played blues and gave a special feeling of happiness and exuberance. He played music from other composers but gave it his own identity. It’s pure swing. I have a lot of experience playing the Basie repertoire in great groups like drummer François Laudet’s big band. On Swinging The Count, it was a very great experience to play with the amazing Alvin Queen. He has a real black beat. My goal was to celebrate Count Basie’s music in trio form. That has never been done with this line-up. Oscar Peterson did quartet recordings and there’s the two Count Basie records with Ray Brown and Louie Bellson. I love the Basie recordings from the 1950’s and 1960’s because of the maturity of Basie and the sound of the bands. Amazing quality and great composers and arrangers like Quincy Jones and Neal Hefti.”

He’s the kind with good faith in mainstream jazz. “It’s perfectly possible to create new things in the mainstream repertoire. Essentially, jazz is very simple. It’s like Alvin Queen told me: ‘It’s just swing and melody!’ Of course, you can have different inspirations like African or Asian music or whatever and create a lot of things. But basically it’s all about context. I love someone like Benny Green. Each recording is always musical, lively and in the tradition.”

The generation of Caillaud, inspired by the resurgence of interest in classic jazz, music that had balls and grew from the earth like potatoes and cucumber and chili pepper, was embraced by the old guard. “It was important to me to play with older musicians and listen to their stories. I was friends with Pierre Michelot. He told me: ‘When I was young, I started to play with older musicians, I learned the repertoire and I learned to play. Then I became a veteran. But it was impossible to play with the young people in the 1980’s. They didn’t know the repertoire and only played their own compositions.’ It was frustrating for him to deal with the fusion period. But he was happy when my generation arrived.”

And now Caillaud spreads the word to inspiring youngsters around town. Lucky little boogers!

Cédric Caillaud

Discography:

- June 26 (Aphrodite 2006)

- Emma’s Groove (Aphrodite 2009)

- Swinging The Count (Fresh Sound Records 2013)

- With Respect To Jobim (Fresh Sound Records 2020)

Check out Cédric and his albums on Fresh Sound here.