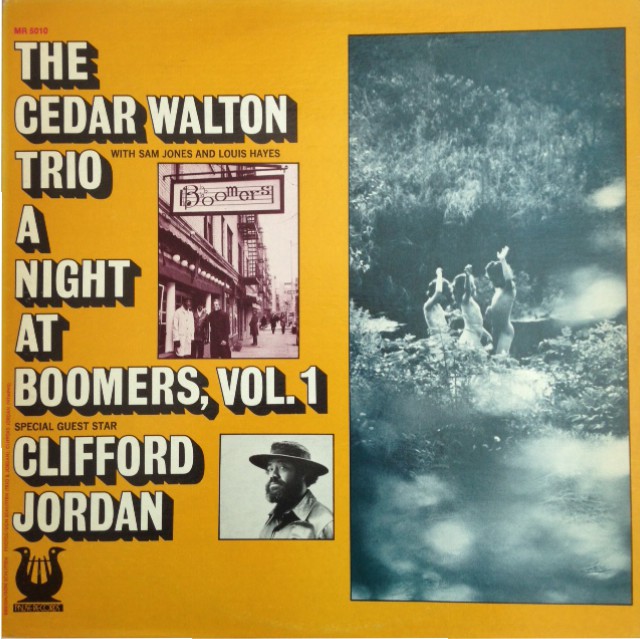

Mainstream jazz at its most fluent, refreshing and adventurous. That is A Night At Boomers Vol. 1 & 2 by The Cedar Walton Trio featuring Clifford Jordan.

Personnel

Cedar Walton (piano), Clifford Jordan (tenor saxophone Vol. 1 A1, A3, B1-4; Vol. 2 A2, B1-3), Sam Jones (bass), Louis Hayes (drums)

Recorded

on January 4, 1973 at Boomers, New York City

Released

as Muse 5010/5022 in 1974

Track listing

Volume 1

Side A:

Holy Land

This Guy’s In Love With You

Cheryl

Side B:

The Highest Mountain

Down In Brazil

St. Thomas

Bleecker Street Theme

Volume 2

Side A:

Naima

Stella By Starlight

All The Way

Side B:

I’ll Remember April

Blue Monk

Bleecker Street Theme

Gary Giddins: “Where is jazz going?”

Cedar Walton: “It’ll go wherever we take it. We’re the masters of it. And wherever my colleagues and I feel like going tomorrow.”

The time is January 4, 1973, the place is Boomers in Greenwich Village, NYC, the club that, by all accounts, overflows with knowledgeable jazz fans. The paranoiac and grumpy Republican, Richard Nixon, is in the Oval Office. The burglaries at the headquarters of the Democratic Party take place in May 1972. Reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein sink their teeth into the case. It’s a pressure cooker. The termination of the Vietnam War is long overdue. The number of casualties has been highest among blacks. The army is still segregated. Blacks here, whites there. And here means low in the hierarchy – straight from the assembly line of the Ford factory to the battlefields. Few if any black men wear stripes and play cards in the mess. It’s still, well, a mess.

James Brown is now singing that crack is ruining the hood. The seeds of gangsta rap are sown. White rock is fed to the general public, the corporate smile grows broader and broader by the minute. In jazz, fusion is the big thing, Miles Davis and Weather Report the big names. Living jazz giants are doing fine: Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz. Dave Brubeck is a star. In general, straight-ahead jazz is having a hard time. Regardless of the passionate promotional and educational efforts of Cannonball Adderley, John Lewis, critics, and the occasional write-up in Time Magazine, Average Joe has by and large been (kept?) ignorant of jazz, the beautiful musical art form that, though not exclusively of black origin, can’t be separated from the tormented past and lively culture of the black race and would have been void without it. Amidst the general turmoil, a group of outstanding innovators and stylists, either in the USA or as expatriates in jazz-minded Europe, keep the flame of classic jazz burning: Kenny Clarke, Dexter Gordon, Clark Terry, Gerry Mulligan, Johnny Griffin, Zoot Sims, Art Pepper, Benny Bailey, Phil Woods, Slide Hampton, Jim Hall, Joe Pass, Art Farmer.

And pianists like Tommy Flanagan, Ray Bryant, Kenny Barron. Cedar Walton. Walton, born in Dallas, Texas, was supposed to play on his friend John Coltrane’s landmark album Giant Steps. But while he was out of town, Tommy Flanagan got the call. Walton came into prominence as the pianist of Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers. A gifted writer, Walton penned future standards as Mosaic, Ugetsu, Bolivia, Mode For Joe and Holy Land. Now it’s 1973. Walton, already a very accomplished player in the 60s, matured into a commanding maestro – it has slowly but surely dawned on me that the work of the Flanagans, Bryants, Barrons and Waltons gained considerable depth in the second phase of their careers. Much to our delight.

Crew of Boomers: Walton, craftsman with amazing skills, skills subservient to flexible, rich lines, unceasing drive and phrases crusted with the grit of the honky-tonk floor. Bassist Sam Jones and drummer Louis Hayes. Extraordinary rhythm engine since The Cannonball Adderley Quintet. Hayes the former drummer of Horace Silver’s group, who elevated ‘small ensemble’ hard bop drumming to its ultimate level. Tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan, who matured from Rollins-styled player to volatile Mingus associate and individual personality that delivered the remarkable Glass Bead Games eight months after the Boomers gig.

Glass Bead Games – extension of John Coltrane’s music – tapped into mankind’s subconscious longing for beauty and unity. It’s uniquely organic. A Night At Boomers, regardless of progressive tinges, is more concerned with redefining mainstream jazz. It does, however, possess a wholesome vibe, perhaps because everybody felt it, musicians and audience alike. If this was an exemplary performance of the Cedar Walton Trio featuring Clifford Jordan, and there is not much room for doubt, I envy those who were able to experience it night after night. The Baby Boomers comprised a lucky crowd.

Boomers bristles with invigorating interpretations of standards, All The Way, Down In Brazil and Charlie Parker’s Cheryl among them. Stella By Starlight and I’ll Remember April are souped-up Kreidlers suddenly taking swift turns like the slickest of Kawasakis. The first four minutes of April are reserved for Sam Jones’s meaty and lyrical bass story, the second part for Clifford Jordan’s fiery tenor playing. Clifford Jordan’s balanced but potent blues playing is the topping of Thelonious Monk’s Blue Monk’s leisurely pace. The archetypical juxtaposition of the Carribean rhythm and uptempo 4/4 sections of Sonny Rollins’s St. Thomas are handled just that extra specially, the Latin part boisterous, the 4/4 part lightning fast and crisp as crackers on Sunday morning. Walton reacts accordingly, switching smoothly from percussive variations to a quicksilver update of Bud Powell.

A joy. The best, however, is yet to come. At least, the tracks that I usually have been immediately drawn to are Holy Land, The Highest Mountain, This Guy’s In Love With You and Naima. The composition of Holy Land is a stroke of genius. The simple and lovely melody – you can hear a child humming it in the playground – is introduced and ended by Walton’s glamorous Bach-like outlay of the chords, which flows smoothly in and out of the tune’s mid-tempo bounce. Whatever the holy land means from Walton’s perspective – Israel for the chosen ones that fled from Egypt, the promised land of Dr. Martin Luther King – Walton obviously had good hopes of discovering it one day.

Perhaps he also longed to reach The Highest Mountain, an equally beautiful, modal-tinged composition. He’s assisted on his travels by Clifford Jordan (Led by Joshua, the tribes of Israel crossed the river Jordan…), who tells one of his all-time great stories. Jordan gives pleasures in measured doses. His tone doesn’t push you against the wall, it’s relatively thin, light as a day in early Spring. His phrasing is agile like the movements of the antelope and his smooth but forceful message is interspersed with sudden, emotionally charged grunts and growls. One hears him searching, investigating, wondering, smiling, pondering and, finally, finding something he deems worthy for a new search. A great artist.

Cedar Walton reaches new levels of trio playing. There’s an endless stream of long lines and ideas during This Guy’s In Love With You, which is started in a funky vein, developed into a crisp groove. Walton is exuberant and his superlative skills are balanced by commanding blues figures. John Coltrane’s Naima never fails to touch my heart, Walton’s voicing and lines a rare, heartbreaking thing of beauty. I have to go with Gary Giddins, who says in the liner notes that Walton is ‘meshing softness with command. It has the cumulative effect of a rose unfolding its pedals.’

This group with near-telepathic synergy effortlessly moulds contemporary jazz to its feelings and highly developed aesthetic.