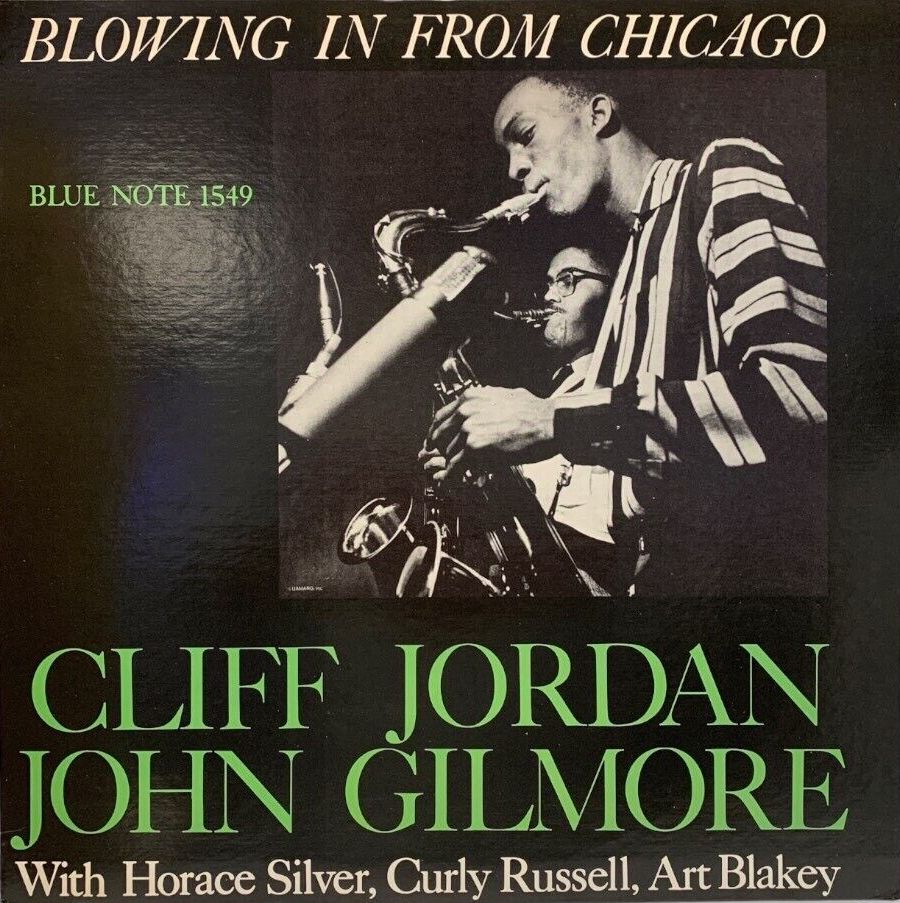

Upcoming Chicagoans blend effortlessly with mighty New Yorkers for what has become one of the hard-swinging Blue Note classics.

Personnel

Clifford Jordan (tenor saxophone), John Gilmore (tenor saxophone), Horace Silver (piano), Doug Watkins (bass), Art Blakey (drums)

Recorded

on March 3, 1957 at Rudy van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, New Jersey

Released

as BLP 1549 in 1957

Track listing

Side A:

Status Quo

Bo-Till

Blue Lights

Side B:

Billie’s Bounce

Evil Eye

Everywhere

Although the title couldn’t have been more straightforward, I have always felt a sense of mystique regarding Blowing In From Chicago. See them coming, black cowboys on horseback, axe in hand, towering over the potholes of Broadway. Of course, in reality, someone drove Clifford Jordan and John Gilmore through the Lincoln tunnel, via the New Jersey Turnpike to one of the prime places of jazz recording history, Rudy van Gelder’s studio in the house of his parents in Hackensack. Benevolent couple, keen and self-willed optometrist-turned-engineer son, who spent more tape that toilet paper.

Blue Note label boss Alfred Lion had coupled the two Chicagoans with stalwarts Horace Silver, Curly Russell and Art Blakey, reunion group of Jazz Messengers. After all, although not strictly a Messenger, Russell had been bassist on Horace Silver’s Horace Silver Trio in 1953 featuring Blakey and on Art Blakey Quintet’s A Night At Birdland Volume 1-3 in 1954 featuring Horace Silver, among other associations with Silver and Blakey in the bop-to-hard bop-period. Jazz Messengers-founder Horace Silver had struck out on his own in 1956, leaving the baton to booming Blakey.

Happy reunion, success guaranteed. How did Lion come up with the idea of getting Jordan and Gilmore into the recording studio on March 3 in 1957? Likely at the advice of Johnny Griffin. Griffin had recorded his Blue Note debut album Introducing Johnny Griffin in April 1956 and had been high school mates of Jordan and Gilmore at DuSable in Chicago under the tutorage of famed teacher “Captain” Walter Dyett. Blowing was Jordan’s first session for Blue Note. The same year, he reappeared as co-leader (John Jenkins, Clifford Jordan & Bobby Timmons) and leader (Clifford Jordan, Cliff Craft).

Surprise pick John Gilmore is best known for his long association with Sun Ra from 1953-93. The Summit, Mississippi-born Chicagoan predominantly played clarinet in Army bands from 1948-52 and subsequently joined the Earl Hines band on tenor in 1953. One of the figureheads of Sun Ra’s quirky and esoteric big ensemble realm, Gilmore rarely recorded in the small ensemble format.

However, a closer look reveals that Gilmore delivered high-quality, original contributions to small bands, Blowing being the excellent starter. After a long silence, Gilmore added his tenor flavors to Freddie Hubbard’s The Artistry Of Freddie Hubbard (1962), McCoy Tyner’s Today And Tomorrow (1963), Elmo Hope’s Sounds From Ryker’s Island (1963), Paul Bley’s Turning Point (1964), Art Blakey’s ‘S Make It (1965), Andrew Hill’s Andrew (1964) and Compulsion (1966), Pete LaRoca’s Turkish Woman At The Bath (1967) and Dizzy Reece’s From In To Out (1970). His versatility is striking. He’s at home in the post-bop environment but also excellently contributes, clipped phrasing and off-beat developments of motives and all, to avantgarde recordings, notably Hill and Bley. His playing on LaRoca’s Turkish Woman is very powerful and in sync with the drummer’s exotic concept.

No doubt, certainly after all these years where Blue Note has become synonymous with jazz, Blowing is his best-known small band recording. In the liner notes, Joe Segal mentions that both Jordan and Gilmore were influenced by Lester Young, Don Byas, Lucky Thompson, Gene Ammons, Dexter Gordon, Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins. On another record, namely Johnny Griffin’s Blowing Session, Leonard Feather simply classifies Jordan and Gilmore as respectively influenced by Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane. At that phase in his career, Jordan, who would become the revered creator of such original works as Glass Bead Games, surely professed a preference for the Rollins sound and style. But Gilmore and Coltrane? In 1957? Seems unlikely and seems more likely that Gilmore was influenced by the above-mentioned cats that blew in from elsewhere or simply came from Chicago like Gene Ammons.

The early 1960s is another matter entirely. Sources like the Coltrane bio Chasin’ The Trane and Coltrane’s interview with Frank Kofsky in 1966 reveal that there has been mutual influence between Gilmore and Coltrane. They met at Monday night sessions at Birdland in 1960, where Gilmore teached Coltrane techniques to reach high notes and Coltrane showed his tenor colleague the ropes of unique harmonies. It is well-known that Coltrane was inspired by Sun Ra. Reportedly, Coltrane had listened extensively to Gilmore, whose playing style on Ra’s records of the late 1950’s directly influenced Coltrane’s new direction of his Chasin’ The Trane recording. It is much harder to pinpoint the influence of Coltrane on Gilmore, which Feather, in his revised 1970’s edition of the famed Encyclopedia of Jazz, reluctantly admits. It’s much more difficult to push the Little Man Influences Little Big Man story down people’s throat than vice versa.

So much for jazz influences and jazz popes, here it is March 3, 1957, stormy weather of swing, a couple of hip tenors aboard the Blakey Boat, captain Art, helmsman Horace and boatswain Curly delivering the goods of a well-documented classic. As producer and writer Michael Cuscuna wrote in the liner notes to Blowing’s 2003 CD reissue, the balance between tunes is perfect, the set being divided between hard swinger (Chicagoan John Neely’s Status Quo) and Latin-tinged tunes (Jordan’s Bo-Till) that are based on familiar changes, contemporary standard and minor-key blues (Gigi Gryce’s Blue Lights and Jordan’s mellow Evil Eye), typically keenly structured Silver original (Everywhere) and major-key bop romp (Charlie Parker’s Billie’s Bounce).

Admirably unperturbed by the gusty winds of Blakey, Jordan and Gilmore acquit themselves very well, Jordan employing a smooth tone and semi-lazy beat, Gilmore working with a harder sound and vertical, dynamic lines. The secret of Blowing’s success, could it be anything else, lies in the presence of Art Blakey. Ever heard a sizzling ride beat as in Status Quo? Ain’t no status quo! Major sea changes in the time frame of merely 5 minutes, incited by furious rolls and tacky rimshots, right on the dot. Blakey’s intro of Billie Bounce, too, is unforgettable and, lest we forget, followed up by sustained, hard groove. It also features a long, fervent solo by Silver.

Made 63 years ago, Blowing In From Chicago remains an unbeatable record, perfect kick start of the day or evening, like a strong and hot cup of Portuguese espresso.