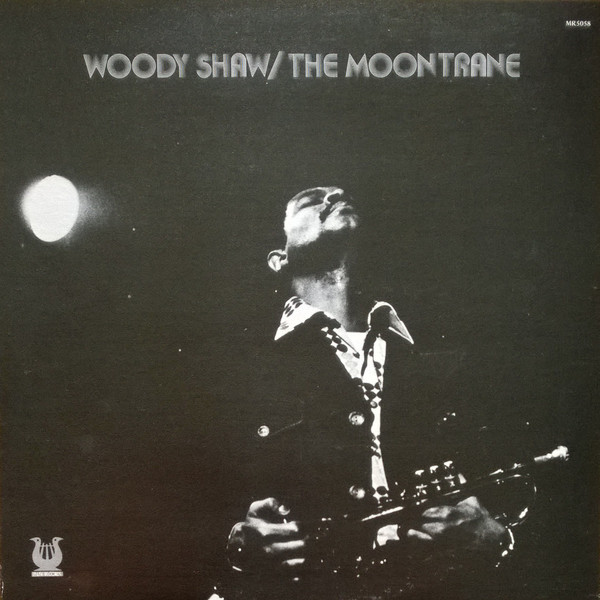

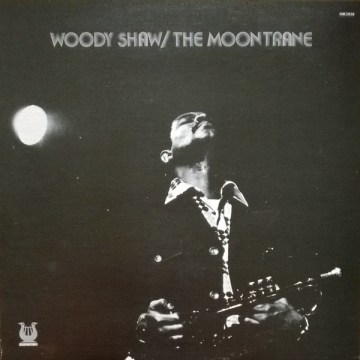

Woody Shaw’s killer tune The Moontrane kick starts his namesake album on Muse, a sublime example of progressive mainstream jazz of the mid-70s.

Personnel

Woody Shaw (trumpet), Azar Lawrence (tenor saxophone, soprano saxophone), Steve Turre (trombone), Onaje Allen Gumbs (piano, electric piano), Cecil McBee (bass A2, B2), Buster Williams (bass A1, B1), Victor Lewis (drums), Guilherme Franco, Tony Waters (percussion)

Recorded

on 11 & 18 december, 1974 at Blue Rock Studios, New York City

Released

as MR 5058 in 1975

Track listing

Side A:

The Moontrane

Are They Only Dreams

Tapscott’s Blues

Side B:

Sanyas

Katerina Ballerina

Some have argued that the tragedy of Shaw’s life was the undervaluation of his genius. There’s truth in this statement. The name might ring a bell. But although Shaw was nominated for a Grammy Award for Rosewood in 1978, the average listener would never put Shaw, as far as trumpeters go, as the exclamation mark on the modern jazz sentence that begins with Dizzy Gillespie and is followed up by Clifford Brown and Miles Davis – Davis is part of the sentence not so much on a technical basis but because of his originality and vision. The average music fan has usually heard about legendary “subordinate clauses” like Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard and Chet Baker. Probably even hardcore jazz fans have listened more to those three than Shaw. Shaw came on the scene in the sixties but matured as a leader in the 70s, the synthesized decade that is without the revolutionary spark of bebop or the monochrome charm of hard bop and not as conducive to myth-making.

We all have our favorites, even, and with justified reason, others than mentioned above. But the exclamation mark is set in bold type by fellow musicians, who have championed Shaw as ‘the last great innovator on trumpet’. Max Roach said he had never heard anybody like Shaw, who had perfect pitch, photographic memory and a simply God-given array of talents that hint at ‘high intelligence’ and definitely are proof of a highly gifted musical intellect that effortlessly incorporated avant-garde concepts as polytonality and modality in his style. Shaw is a bridge between the classic age of modern jazz and the young lions of the 80s, many of who are now middle-aged statesmen, like Bryan Lynch, Wynton Marsalis, Nicholas Payton, Wallace Roney, Valery Ponomarev and Jarmo Hoogendijk.

Let’s hear it from Michael West, NPR:

“Shaw was a virtuoso who restructured the way trumpet players move between long intervals, and wrote his own harmonic and melodic language using notes outside the chords (a technique known as “side-slipping”).”

And Doug Ramsey, Rifftides:

“Shaw reached a level of expressiveness, headlong linear development and freedom from post-bop conventions that was not only ahead of his time; this music from three and four decades ago is ahead of much of the rote, formulaic jazz of our time. (…) Shaw was at once a liberator of the music and a preserver of tradition.”

Ramsey’s assessment rings through when listening to the series of live CD sets (yuk but hey) that have been released over the years. Above all, his live performances from the 70s and early 80s showcase remarkable intensity and hi-voltage stories that surge ahead with unstoppable force like the subway train of The Taking Of The Pelham 123. At the same time nothing of Shaw’s elegance is lost. Then there’s his bright, tart tone, ringing clearly like the bells of St. Mark and his punchy attack, resembling the chutzpah of the strongest kid in class. Moreover, Shaw wrote a number of lasting tunes like Stepping Stones, Rosewood and Little Red’s Fantasy.

Maturity as a leader came late at the dawn of the 70s, but Shaw was already very active as a sideman in the sixties. He debuted on Eric Dolphy’s Iron Man and burst on the scene with his feature on the Blue Note classic album by organist Larry Young, Unity, for which the then 18-year old trumpeter wrote three compositions: Zoltan, Beyond Limits and The Moontrane. Talkin’ about lasting tunes! Shaw hit the hard bop mark as band member of the Horace Silver group. A session for Blue Note featuring Joe Henderson in 1965 was shelved. It was eventually released on Muse as In The Beginning in 1983. He kicked off his solo career in 1970 with the double LP Blackstone Legacy, a charged post-bop alternative for those that deem Bitches Brew languish. And indeed overrated. That includes yours truly.

At the tail end of 1974, Shaw recorded The Moontrane, aptly named after his unforgettable composition. It’s a cutting edge album, a hefty dose of mid-70s progressive jazz that in a sense owes much to the concept and passionate approach of John Coltrane. Oh how I would’ve loved to hear Shaw perform with Coltrane! Why wasn’t that in the stars? The stars would’ve been obscured by miraculous fireworks! On The Moontrane, Shaw is assisted by tenor and soprano saxophonist Azar Lawrence, definitely a fiery, Coltrane-influenced player, with a tad of Joe Henderson. Bon appetite. The band further includes trombonist Steve Turre, pianist Onaje Allen Gumbs, bassists Buster Williams/Cecil McBee and drummer Victor Lewis. The trombone is the tart icing on the frontline cake, that bit of extra punch. The band is a flexible, flamboyant outfit perfectly suitable for Shaw’s challenging shenanigans.

The title track, The Moontrane, recorded 10 years after Larry Young’s Unity, is reclaimed beautifully by Shaw & Co. The exotic groove, Sanyas, is chockfull of highlights: the beautiful, Eastern-tinged introduction by bassist Buster Williams, slides and bends and all; the quaint blend of modernism and the gutsy feeling of the Ellington trombonists of Steve Turre; the plethora of flowing and staccato phrases by Shaw. Shaw’s continuously curious and surprising placing of notes puts you on the wrong foot and that’s a delight. His notes are like the pinches of the acupuncturist’s needle, a dead perfect stimulus.

Are They Only Dreams shifts from a lithe Latin beat to a Hancock/Corea-ish pulse, an apt ambience for Allen Onaje Gumbs, whose lines fall down on you like drops from a little waterfall. Katrina Ballerina is a lovely melody in waltz time. The tension is heightened by turbulent clusters of double timing by Shaw. The album is completed by Tapscott’s Blues, perhaps the only tune you do not desperately need to spin back to back, but a lively romp nonetheless. 1974 may not have been the best year in jazz. Right? Right! But Shaw definitely was keeping the flame burning.

At least, until the candlelight was blown out for him by The Gusty Wind in the 80s. Trumpeter Woody Shaw never returned home to Newark, New Jersey after visiting a performance of Max Roach at the Village Vanguard in New York City in February 1989. Turned out he was caught by a subway train, which severely injured his arm and head. His arm had to be amputated. After a long, partly comatose spell in the hospital, Shaw eventually passed away by the causes of kidney and heart failure on May 10, 1989. Shaw was 44 years old.

The Moontrane is not available on Spotify. (You see, general neglect!) However, the full album is available on YouTube, listen here.