Fine pianist from the periphery of the jazz landscape recorded his third album on the incomparable Atlantic label.

Personnel

Eddie Higgins (piano), Richard Evans (bass), Marshall Thompson (drums)

Recorded

in 1965 at Universal Recording Corporation, Chicago

Released

as Atlantic 1446 in 1965

Track listing

Side A:

Tango Africaine

Love Letters

Shelley’s World

Soulero

Side B:

Mr. Evans

Django

Beautiful Dreamer

Makin’ Whoopee

Eddie? You mean, the Eddie? Sure, man, you don’t have to tell me who is who. Eddie is a fine pianist, we used to hang at the Brass Rail, colorful guy.

Perhaps this is the question-and-answer query of quite a few jazz dinosaurs. Not mine though, to be honest. It was only after discovering Eddie Higgins on an online jazz forum that I started to listen to him and finally acquiring some of his records, including Soulero. And it was only after I started to dig into his career info that I found out, oh, it’s thís Eddie, I heard him but it somehow didn’t register. Because Mr. Higgins played on Lee Morgan’s Expoobident, Wayne Shorter’s Wayning Moments and Wes Montgomery’s One Night In Indy. That’s right. Not bad. By the way, the late Wayne Shorter asked him back for 2002’s All Or Nothing At All and 2013’s Beginnings.

It all started in Chicago for the Cambridge, Massachusetss-born Higgins. A pianist that was versed in swing and bop and led various bands in The Windy City opposite fellows like Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Dizzy Gillespie and Wes Montgomery. He played with the likes of Coleman Hawkins, Jack Teagarden, Oscar Peterson and Sonny Stitt and was the house pianist at the high-profile London House from 1957 to the late 1960’s. He made quite a few records in the USA with Milt Hinton, Rufus Reid, Ray Drummond. It seems that he was very popular in Japan, having released 20+ records on the Venus label with, among others, Scott Hamilton from 2000 till 2008. Where was I? I don’t have a clue. Probably, as cult country star and the world’s funniest whodunnit-writer Kinky Friedman would say, out there where the buses don’t run.

I was alert enough, though, to notice an online comment on Higgins by jazz buff and reviewer Randy L. Smith. Smith, based in Japan, saw him perform in Fukusaki in 2006 and 2007. He provided me with an interview with Higgins in Cadence, written by Dan Gould. Interestingly, Higgins, who lived in Florida by the time of the interview, tells of his surprising refusal to act upon the request of Art Blakey to join his band in 1960. It was just after Higgins’s feature on the Morgan album on October 14, 1960, which included the famed Buhaina. In theory, Higgins would join the then-current line-up of Morgan, Shorter and Jimmy Merritt and would be the replacement of Bobby Timmons. But he refused, seeing one huge plus – immediate acclaim and world-wide touring – but a lot of negatives: (with kind permission of Dan Gould)

“First of all I’ve got a great job here in Chicago in the London House and my kids were very little at that point. And the idea to be on the road all the time and not seeing my children grow up is a negative. Number two, this is pretty much an all-junkie band and I’m not only nót a junkie, I don’t even drink or smoke pot or anything at all. I would be out of the loop as far as the social life of the band, plus the fact that I’m the only White guy in the band. And at that time in jazz history there was a very strong Crow Jim feeling that if you’re White, you couldn’t play. And obviously they knew I could play or I wouldn’t be on these record dates or asked to join the band, but still there’d be a… definite racial bridge to cross there working with the Jazz Messengers and playing in probably mostly Black clubs for mostly Black audiences and so forth. And third, I heard by the grapevine that when payday came the first guy that got the money was the connection for the heroin, and not just Blakey but the rest of the band, too. And if there’s any money left over then they pay the hotel bill and if there’s anything left over from that then maybe the guys will get a few bucks. I had a family and rent to pay and insurance payments.”

Blakey replied: ‘You’re kidding’. Because as Higgins says, to get an offer from The Jazz Messengers is like being touched on the shoulder by God. In the end though, it seems a perfectly logical decision.

Atlantic somehow got wind of Higgins. Perhaps, Ahmet or Nesuhi Artegun were conscious of the fact that Higgins served as producer for Chess Records. Anyway, they got him in the Universal Recording Corporation studio in Chicago with his long-standing rhythm section of bassist Richard Davis and drummer Marshall Thompson.

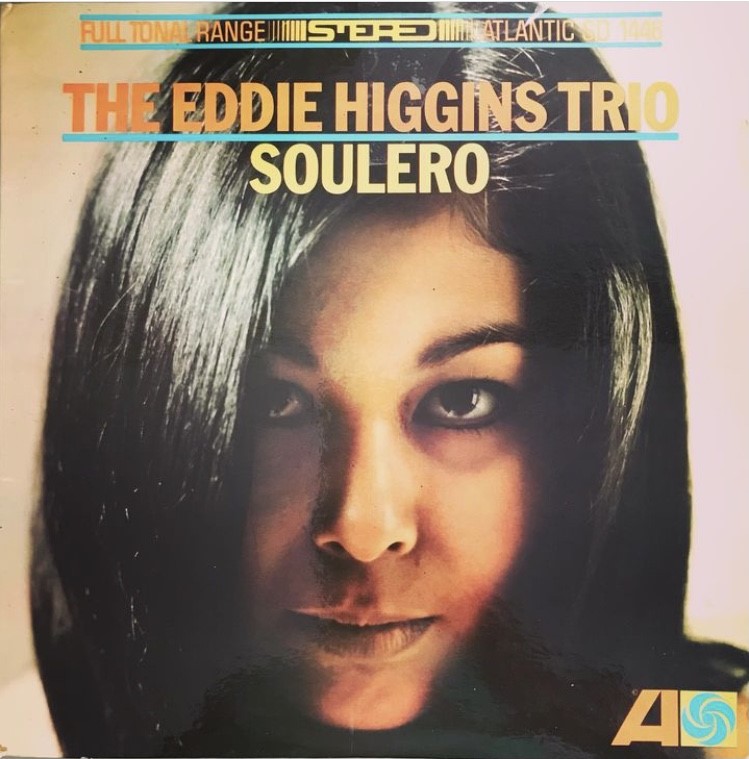

Soulero was the end result. Hip sleeve. The look of love sells, doesn’t it. Atlantic was pushing Higgins in the direction of soul jazz. There is a decidedly Ramsey Lewis-style vibe. Richard Evans and Marshall Thompson were worthy and prolific contenders in the jazz business. They are sophisticated while working up quite a storm. There is a notable diversion of groove, divided between Higgins’s Tango Africaine, the ‘bolero’ of Soulero and the bass-driven swinger Mr. Evans. Folk melody Beautiful Dreamer and Bill Traut’s Shelley’s World represented the lighter touch of Higgins. A baroque introduction defines Love Letters. Higgins intriguingly works his way through the bridge of the iconic, John Lewis’s Django. Makin’ Whoopee is made into a nifty and entertaining flagwaver and is developed from nice ‘n’ easy to fast and, finally, furious Speedy Gonzales-tempo.

Certainly not a waste of time. The Ertegun Bros seemed to agree, as they released The Piano Of Eddie Higgins the following year, even going to the expense of adding an orchestra. They knew he was a fine pianist. But there are many fine pianists out there and Higgins seemed to have a knack of flying under the radar.

Listen to Soulero on YouTube here.