SPOTLIGHT ON – JIMMY ROWLES

(in cooperation with Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven)

It’s no use to make anything holy if only for the inherent failure of leaders and followers to meet the standards of deification. Holiness also implies submission to a cause one dares not criticise. So jazz and its leaders are not holy. It’s easy to succumb to the impulse. I have to confess that on a number of occasions, I have typified the great Charlie Parker as “The One” and “part rebel rouser part Messiah”. No doubt a blasphemous analogy in the view of the religious community. No doubt a definition that Charlie “Yardbird” Parker would take with a grain of salt before carrying on with one of his unforgettable bird flights. Then again, most likely something true jazz aficionados would not blame me for posing.

Holiness may be hyperbole but the value of jazz as a transcendent and spiritual force is immense. By nature, jazz breaks borders. In the arena of club or studio, it doesn’t in principle matter if you’re black or white, young or old, or which country you come from. As long as you understand the beautiful language of jazz. However, the business side of jazz – it might be a general cultural phenomenon – has always been hype-driven. And so it has come to be that young “new stars” are signed to major labels overnight, while middle-aged masters struggle on the outskirts of the jazz landscape. Sometimes, they float to the surface as “elder statesmen” on the international stage with the help of encouraging colleagues, promoters, journalists, A&R people and club owners. At that moment, you will most likely read an article in the mainstream media that reflects the saying, “wow, that old-timer sure knocks everybody for a loop!”. As a consequence of the business’s age discrimination, crackerjack and influential performers as Joe Henderson, Tommy Flanagan, Charles McPherson, Lou Donaldson and Dee Dee Bridgewater have in their 40s performed under the radar for years, to come out on top in the last stage of their careers.

Sometimes they’re there all the time, under the radar, like Jimmy Rowles, who traveled along a very curious route with generous outpourings of piano artistry. In 1973, as Gary Giddins, jazz critic sui generis, noted in Visions Of Jazz (Oxford Press, 1998), Town Hall billed Rowles as “California’s greatest jazz pianist” preceding a Johnny Mercer concert. A tad chauvinistic, no doubt, but not such a crazy idea at all, even considering the fact that Oscar Peterson was based on the West Coast. In the mid-70s, Rowles already had maintained a career for twenty-five years and after a hiatus in the 60’s relocated to New York. Half of the audience in the clubs where he had residencies, mostly Bradley’s and The Cookery, consisted of hyper-attentive pianists.

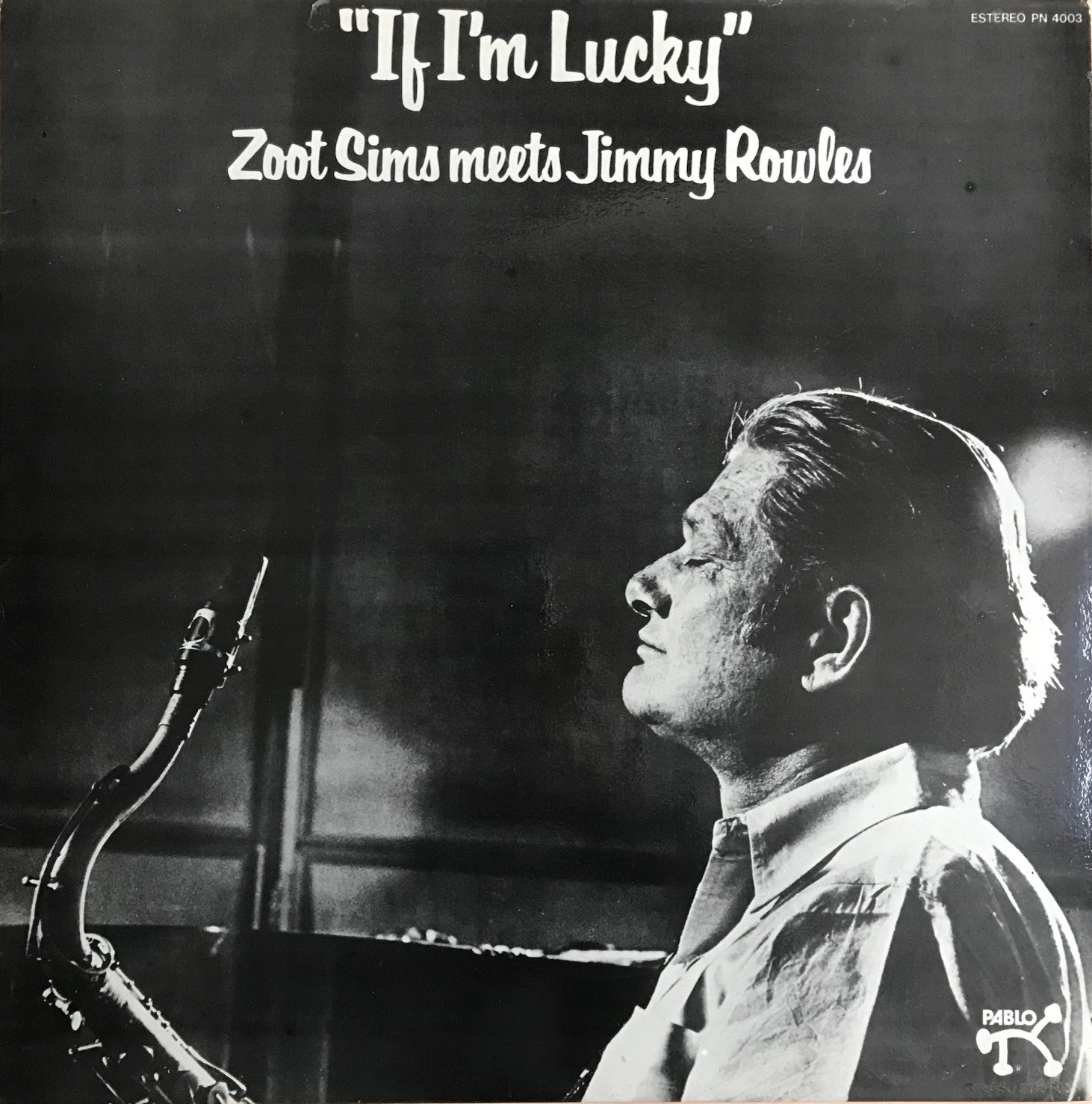

His underground reputation makes the question who really is Jimmy Rowles rather problematic. This is how far I go: He’s omnipresent as a recording artist yet many of his albums as a leader are rarities. Rowles, born James George Hunter in Spokane, Washington in 1918, started his career as early as the early 40’s, touring with Slim Gaillard and Lester Young, Benny Goodman and Woody Herman. He hit his stride in Los Angeles, which was rife with opportunities to record and work in the studio system. Rowles recorded with Benny Carter, Buddy Rich, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Stan Getz, Gerry Mulligan, Ben Webster, Shelly Manne, Al Cohn, Pepper Adams, Nat King Cole, Barney Kessel, Lee Konitz and many others. He had a special rapport with tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims, cooperating on Sims’s excellent Pablo recordings in the late 70’s.

As an accompanist of singers, Rowles was non-pareil and in constant demand. He supported virtually all the great singers: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Carmen McRae, Peggy Lee and Diane Krall among others, whom Rowles and Ray Brown encouraged to sing. He’s featured on Billie Holiday’s Songs For Distingué Lovers from 1957. Rowles sang himself as well, in a conversational style that is not virtuosic but charming and with a grittiness that is leavened by Billy Holiday-ish legato phrasing. He sings a couple of songs on his best-known record, The Peacocks, featuring Stan Getz from 1978.

His knowledge of songs was unparalleled. Rowles knew more than two thousand songs and included many oddities in his repertoire. During his lifetime, he gradually developed a library of songs and charts in Los Angeles, a treasure trove for musicians and producers in need of half-forgotten songs. Rowles had a special fondness for the Ellington/Strayhorn songbook, particularly rarely-performed compositions, which he mined with peerless sense of harmony, melody and characteristics of the solo’s. He also delved into Wayne Shorter’s compositions from the Art Blakey period. Rowles shares with Duke Ellington a detailed use of space and sparse dynamics. He’s an elegant player with intriguing, oblique voicings. Yet both sharp wit (if you listen to him closely, you will imagine that he must have been a fellow with a great sense of humor) and unpredictability stand out in a style that is instantly recognizable. For a description of a unique Rowles solo, I turn again to Giddins, who commented on Rowles’ cooperation with Zoot Sims on Cole Porter’s It’s All Right With Me:

“… played in a rampaging long meter that perfectly captures the give and take between stalwart tenor and daring piano. During Zoot’s first improvised chorus, Rowles pumps him up with chords; in the second, he brings in crescendo tremelos that gather like storm warnings. His own two-chorus solo is of a sort no one else would attempt – a coherent montage of hammered single notes, offhanded dissonances, wandering arpeggios, abrupt bass walks, trebly rambles. When Sims returns, the pianist probes every open space, spurring him until you think they might burst out of orbit.”

(Billie Holiday,

Songs For Distingué Lovers – Verve 1957; Zoot Sims,

If I’m Lucky – Pablo 1977;

The Peacocks – Columbia 1977)

Thank you Mr. Giddins. There’s a shameful lack of mention of Rowles in jazz literature, which leaves detailed info about the life of Rowles hanging in the air. That’s the reason I called Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven, Swiss connaisseur and former manager of bassist Ray Brown and comrade to numerous jazz greats. (Reisser-Beethoven commented on Ray Brown’s Bass Hit recently, see here) Jean-Michel was a friend of Jimmy Rowles and he spills the beans below. Very enlightening.

Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven: “Jimmy should be better known, but he actually was not concerned with fame. He was conscious about his merits. And he was always much in demand anyway. There is no doubt that he is one of the greatest pianists in jazz history. Everybody in the business knows! Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock checked him out in New York and they were astounded. They knew who Rowles was but not that he was that good!

“I admire the way Jimmy took risks as a piano player. Somehow he always came out on top, I’ve rarely ever heard anyone like that. At the same time, his playing is balanced. A great example of his courageous style is his solo on Satin Doll on the Henry Mancini ’67 record. (listen here) He played something totally different than expected, everybody went crazy. And he goes right to the heart of the melody. Did you know that he learned to play stride from Ben Webster? Jimmy and Ray Brown – who also was an excellent piano player – were friends with Ben Webster. Ben learned them to play stride.

“Jimmy played with Lester Young and his brother Lee as early as 1940. And later on with Charlie Parker. Of course, playing with a genius like Parker is a challenge. But Jimmy knew all the great composers, Ravel, Debussy, Bartok, etcetera. So his harmonic sense already was excellent. He said to me: ‘That is what saved me!’

“Jimmy knew all the tunes, and then some. Eventually, Jimmy rented a place to store all his charts, which turned into his Library of Songs. Everybody who wanted to record a tune but forgot how it exactly went turned to his library. It is run by Jimmy’s estate nowadays. Just last year, I forwarded the manager of Michael Bublé to the library.

“I first saw Jimmy perform in 1978 in Nice. Back then festivals were different. Artists played for days on end. So that was a treat. Jimmy was a very funny guy. He loved his drink and was a real party man. Jimmy and Harry “Sweets” Edison used to call Ray Brown “Raymond Fucking Brown”. Haha!

We were talking backstage at the Nice festival in ’78, Jimmy and I and a lot of musicians. A French jazz journalist approached Jimmy, telling him that he really liked the way he sang and that his voice seemed similar to that of Nat King Cole. Jimmy replied with dry wit, “Well, maybe Nat King ‘Cold’. Everybody cracked up.”

Here are a number of must-haves according to Jean-Michel:

(

Jazz Is A Fleeting Moment – Jazzz 1976;

Plays Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn – Columbia 1981;

Duets – Cymbol 1980)

(

Shade And Light – Ahead 1978/Black & Blue 1991; Don Bagley,

Basically Bagley – Dot 1957; Richie Kamuca,

Charlie – Concord 1979)

(Zoot Sims,

Party – Choice 1974;

Scarab – Musica 1978;

Sometimes I’m Happy – Orange Blue 1988)

Jimmy Rowles passed away in 1996.