In the fifties and sixties many rhythm & blues and rock & roll orchestras harboured musicians with jazz chops. Making a living was the main objective. A jam session freed them from their ties now and then. Rarely would a bandleader, who had no dealings with anything other than straightforward backing, let them cut loose. It was only after record companies hired some of these men – sometimes at the suggestion of arrived jazz men – that the jazz world would take notice of their appetizing blend of skills and down-home aesthetic.

Personnel

Fred Jackson (tenor saxophone), Earl van Dyke (organ), Willie Jones (guitar), Wilbert Hogan (drums)

Recorded

on February 5, 1962 at Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

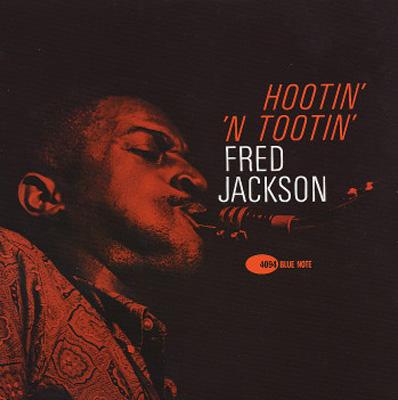

Released

as BLP 4094 in 1962

Track listing

Side A:

Dippin’ In The Bag

Southern Exposure

Preach Brother

Hootin’ ‘n’ Tootin’

Side B:

Easin’ On Down

That’s Where It’s At

Way Down Home

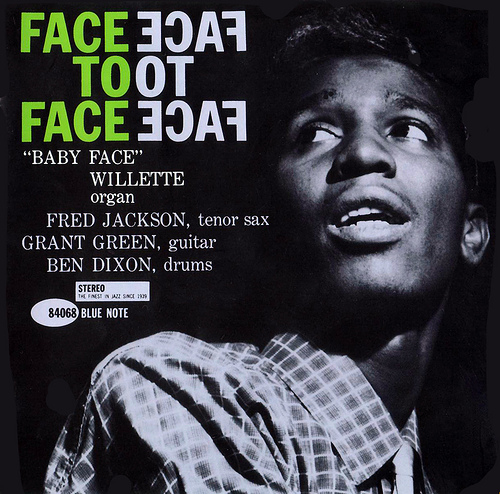

Fred Jackson, who played with Little Richard, Lloyd Price and B.B. King, was that kind of earthy, jazz-oriented player in the r&b realm. People definitely took notice when he blew off the lids of the garbage cans at producer Rudy van Gelder’s Studio in New Jersey, assisting organist Baby Face Willette on the exciting organ jazz album Face To Face in 1961. Thereafter, Alfred Lion, intent on the growth of Blue Note’s soul jazz roster, thought it proper to record Jackson as a leader. The result is Hootin ‘n’ Tootin’.

It’s as down home as it can get. But down home doesn’t mean anything if the protagonist isn’t cut out for it. Fred Jackson certainly lives up to the earthy challenge that the song titles suggest. His wailing style, hard-edged pitch and controlled, relaxed phrasing lend substance to tunes as the slow blues Southern Exposure. Organist Earl van Dyke – who would later become part of the esteemed Motown backing band, The Funk Brothers – puts in an elevating blues solo that ows much to the style of Brother Jack McDuff.

Snappy lines like Dippin’ In The Bag are played out well by a tight group. Wilbert Hogan and Willie Jones are not as fiery and sophisticated as Ben Dixon and Grant Green on Face To Face, but they do a solid job nonetheless. On similar cookers such as Hootin ‘n’ Tootin’ Fred Jackson shows considerable agility, employing both repeated r&b tricks and deft, confident jazz phrasing. Snippets of the styles of Gene Ammons and Arnett Cobb come to the fore.

That’s Where It’s At is another of those appropriate titles. It’s a lilting medium-tempo tune wherein Jackson and Van Dyke trade quotes of the gospel traditional Wade In The Water. It stayed on their mind during this session, as Van Dyke also threw in a snatch of the traditional in Preach Brother. Resembling Nat Adderley’s Work Song, it has the excitement of a congregation. Van Dyke’s solo is a torrent of raunchy figures. Fred Jackson leads the congregation with witty and assertive statements. As far as clear-headed, deft jazz playing is concerned, Fred Jackson certainly was where it’s at. Unfortunately, after recording with organist John Patton in 1963/64 on Along Came John and The Way I Feel, Jackson disappeared from the jazz scene.