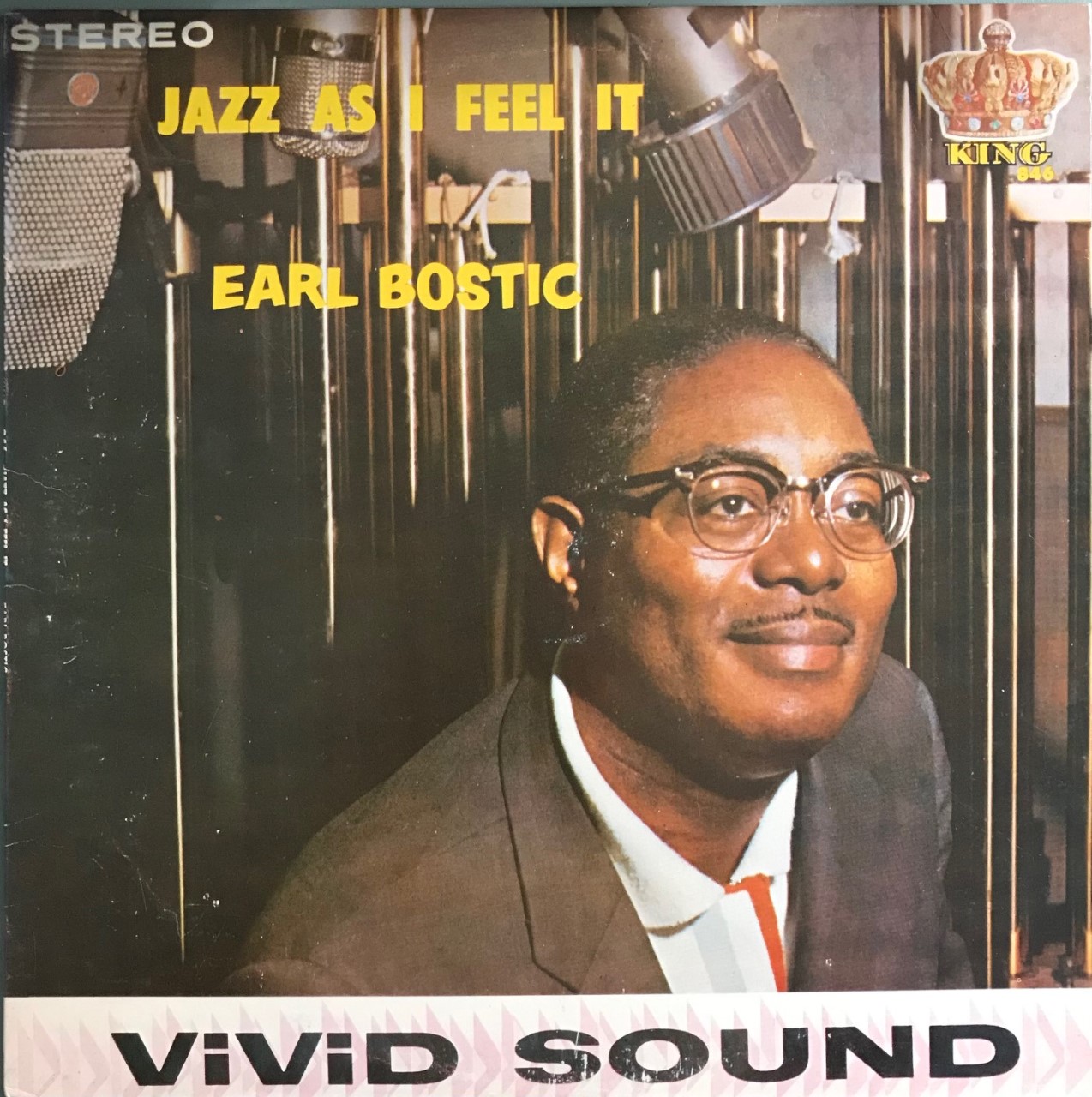

Jazz as Earl Bostic felt it in a rare cooperation with Richard “Groove” Holmes, Joe Pass and Shelly Manne was flawless, blues-drenched and pure dynamite.

Personnel

Earl Bostic (alto saxophone), Richard “Groove” Holmes (organ), Joe Pass (guitar), Herbert Grody or James Bond (bass), Shelly Manne or Charles Blackwell (drums)

Recorded

on August 13 & 14, 1963 at World Pacific Studios, Los Angeles

Released

as King 846 in 1963

Track listing

Side A:

Don’t Do It Please

Ten Out

Telestar Drive

A Taste Of Fresh Air

Side B:

Hunt And Peck

Fast Track

Apple Cake

He walked into bop cradle Minton’s in Harlem in 1951 and learned quite a few cats all about the saxophone. Art Blakey said: “Working with Bostic is like attending a university of the saxophone.”

So, obviously there’s more behind the explosive sax of Flamingo and other hard-hitting rhythm and blues-hits. Bostic, born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1912 and alumnus of Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska and Xavier University in New Orleans, traveled with territory bands in the 1930’s. He worked with Don Redman, Hot Lips Page and Cab Calloway in New York and had a residency with his own band at Small’s Paradise in 1939. Bostic was arranger for Paul Whiteman and Louis Prima before joining Lionel Hampton for a two-year stint. Meanwhile, he had started new bands in the mid-1940’s and following the example of Louis Jordan, seriously started his solo career with a couple of minor hits. His potential was notably fostered by King Records. In total, Bostic would record more than 400 tunes for the Cincinnati-based label of Sid Nathan, including major hits besides Flamingo as Harlem Nocturne, Temptation and Where Or When. Bostic recorded more than thirty LPs for King from 1954 till 1964.

Bostic gained respect from Charlie Parker at Minton’s. Bostic’s groups variously featured John Coltrane, Teddy Edwards, Benny Golson, Stanley and Tommy Turrentine and Blue Mitchell. Coltrane, Golson and James Moody appreciated Bostic’s prowess. In the L.A. studios, Bostic worked with Benny Carter, Barney Kessel and Earl Palmer.

Bostic blew hard and honked relentlessly but his phrases never faltered or broke down and were fluent as the twists and turns from a butterfly, distinguishing him from many of the era’s honking saxophonists. Furthermore, he impressively stretched his alto lines over three octaves. Allegedly, Bostic refused to record everything that he could achieve with the saxophone so as not to give colleagues the chance to copy him.

Not only past masters commented on Bostic’s prowess on the saxophone. I stumbled upon a 2016 column by Dutch saxophonist Benjamin Herman in the excellent Dutch jazz magazine Jazz Bulletin. Herman discusses ‘monster chops’, defining Earl Bostic as the undisputed king. He tells of a Bostic tribute organized by Spanish saxophonist Dani Nelo in Barcelona and that Herman’s part, dedicated to Jazz As I Feel It and A New Sound (the other LP with Holmes and Pass) was an enjoyable and instructive challenge. Afterwards, back in Holland, ultra-young lion Gideon Tazelaar (nowadays lauded by none other than Wynton Marsalis) pointed out the existence of the blasting Up There In Orbit to the Amsterdam-based, UK-born Herman.

Did Bostic use a tenor sax reed on a Beechler mouthpiece? Question perhaps better asked specifically to pros. However, it would explain his tremendous energy. A force that also is evident on Jazz As I Feel It, which consists of two sessions, both with organist Richard “Groove” Holmes and guitarist Joe Pass, with Shelly Manne/Charles Blackwell and Herbert Grody/Jimmy Bond alternating on drums and bass.

Contender to Up There In Orbit might be Telestar Drive, fast-paced bop groove intensified by Bostic, who marries rocket launchings with the roar of the king of the jungle, wild but totally in command, challenged by the energetic Manne. Bostic’s high F ending of Don’t Do It Please – and the journey to it – is madness. Songwriting duties are divided between Bostic and the West Coast-based Buddy Collette and whether it’s slow or medium-tempo blues or a catchy up-tempo rhythm and blues-drenched tune, Pass and Holmes acquit themselves very well, Holmes providing context with various interesting Hammond sounds.

The events surrounding Bostic’s passing were very unfortunate. Bostic owned a club/restaurant, The Flying Fox, in Los Angeles with his wife Hildegarde. However, Bostic was afraid of a possible earthquake and wanted to leave the West Coast. Hildegarde strongly disagreed and filed for divorce in 1965. A week later, Bostic was on tour in the East and completed a residency at the Town House Motel in Rochester, New York. It was there that the monster saxophonist had a heart attack and passed away at the age of 52.

If only Bostic would’ve been able to fulfill his jazz promise at one of those labels that foster elder statesmen like Pablo or Black & Blue. However, making do with Jazz As I Feel It ain’t no punishment.

Listen to Jazz As I Feel It and A New Sound on YouTube here.