Personnel

Bud Shank (alto saxophone, flute), Claude Williamson (piano), Don Prell (bass), Chuck Flores (drums)Recorded

on May 7 & 8, 1956 at Capitol Studio, Los AngelesReleased

as PJ-1230 in 1956Track listing

Side A: A Night In Tunesia/Tertia/All Of You/Theme

Side B:Jive At Five/Softly As In A Morning Sunrise/Polka Dots And Moonbeams/The Lamp Is Low

Shank recorded prolifically on World Pacific in the 1950’s and 1960’s – the beforementioned mix of commerce and real jazz – but as the 1960’s winded down, seemed to have landed in a rut, tired of working in the entertainment business. Perhaps appropriately, Shank burned down the tail end of the decade with his last recording on Pacific, Let It Be, which included songs as Let It Be, Something, The Long And Winding Road, Both Sides Now, Didn’t We and For Once In My Life, featuring Roger Kellaway, Dennis Budimir, Carol Kaye and John Guerin, almost all men and ladies who made good money in the studios and had to resort to play jazz after hours.

The L.A. Four came to the rescue. His association with Ray Brown led to a highly successful period of recording and touring in the 1970’s and 1980’s (1974-82), no less than 10 albums, featuring, subsequently, Chuck Flores, Shelly Manne and Jeff Hamilton on drums and Laurindo Almeida on guitar. Better days. I wondered how it came about that Shank rose from the ashes of the studio grind. As the former Swiss producer Jean-Michel Reisser-Beethoven, former manager of Ray Brown and friend of many now long gone jazz legends, tells it on the phone with Flophouse, it was rather Phenix-like.

“Bud was one of the first call musicians. This guy could read and play anything and he was fabulous on alto, flute, tenor and baritone. He told me about his average working day. You show up at 8 in the morning, get your charts, you got two minutes to read through it, then it’s time to record. And movies had sequences where nothing was written out, you had to watch and improvise, create on the spot. That’s very difficult. Bud was one of the greatest in that field.”

“The problem was, Bud was a jazz guy. After all those years in the studios, he was tired and depressed. It was so bad that he got suicidal. He wanted to quit. His wife was very upset and anxious. She called Ray Brown. That’s what everybody does. There’s a problem? You call Ray. So, eventually, Bud was on the phone with Ray and he said, ‘I wanna do jazz again, let’s get a group together’. Ray said, ‘Well, jazz is in the toilet, nobody wants to hear jazz anymore, let me think about it…’ He said, ‘I got an idea. I’m doing a lot of gigs with Laurendo Almeida, we do classical, bossa, Cuban, jazz, everybody loves it’.

“So, the L.A. Four started after those phone calls. Suddenly, that was the second life of Bud Shank. Ray wanted him to play a lot of flute. Ray had it all figured out, made up an unusual line up of flute/sax and guitar, bass and drums, no piano. It was easy to book, easy to travel and after a while, with jazz somewhat back on its feet in the 1980’s, Bud was a hot ticket. How did Ray and Bud met each other? Bud told me that he first met Ray in 1949, when Bud was in the Stan Kenton band and Ray came to Los Angeles. He met Ray at a JATP concert. Ray told me that everybody talked about this young guy, this motherfucker was supposed to be good. Everybody loved Bud because he was a very honest and funny guy. He didn’t take drugs and he was always on time.”

Reisser-Beethoven continues, in praise of Shank. “He is acclaimed as a great sax player. He’s one of few guys that, though he learned a lot of his lessons, didn’t play like Charlie Parker. He didn’t sound like Parker and was very original. And he is a very great flute player too. I will tell you a story. On many occasions, the jazz players that played for the movies and did the jingles and stuff, they were shit upon by the classical musicians. Often, when the flute parts were to be recorded, the classical guys couldn’t play them. The studio called in Bud Shank. He was the only guy that could play those parts. The classical guys were horrible, they said, ‘call this jazz guy’. They never mentioned his name. Bud came in, took five minutes to play his part, everybody was happy and could go home. One night when he told me this, he was still hurt by the way the way he was treated, practically in tears. I said, ‘Hey man, you fuck them! They couldn’t play it, you could!’ It isn’t like that anymore, but it was like that back then, the jazz guys had a hard time.”

“I organized tours with Bud from 1992 to 1994 with Dado Moroni, Pierre Boussaguet, Alvin Queen. Everybody loved it. It was great because it was well-deserved. He was one of the greats. Once, Benny Carter told me about his five favorite alto players in jazz. Naturally, he picked Charlie Parker and Johnny Hodges as the two greats. The remainder included Cannonball Adderley, Phil Woods, Bud Shank… That tells you something about his stature.”

Shank was back on track. He started to record again as a leader on Concord. And a prolific late career saw him recording on various labels including Contemporary and Fresh Sound. By then, Shank had long since stopped playing flute and focused on alto saxophone. Dutch drummer Eric Ineke, who played with Dexter Gordon, Dizzy Gillespie, Jimmy Raney, Chet Baker, George Coleman and countless others, also played with Bud Shank from the 1990’s onwards. He praises Shank in his book The Ultimate Sideman, noticing a change of tone.

“Bud was special to me, I liked his no nonsense straightforward attitude. (..) The first time I played with Bud was in 1989, together with Bill Perkins on tenor, also from the West Coast. They were not playing West Coast Jazz, they were burning. After the first tour we did many more with the trio of Rein de Graaff. He became more and more a hardcore blower and I think he really wanted to get rid of the West Coast stigma the critics gave him in the fifties.”

“His sound changed because he was getting older, the sound was deeper, he burned harder, swinged harder, he took a lot of chances. When you hear his old records, it’s cleaner and calmer, now he’s got more of everything and he just wanted to blow.”

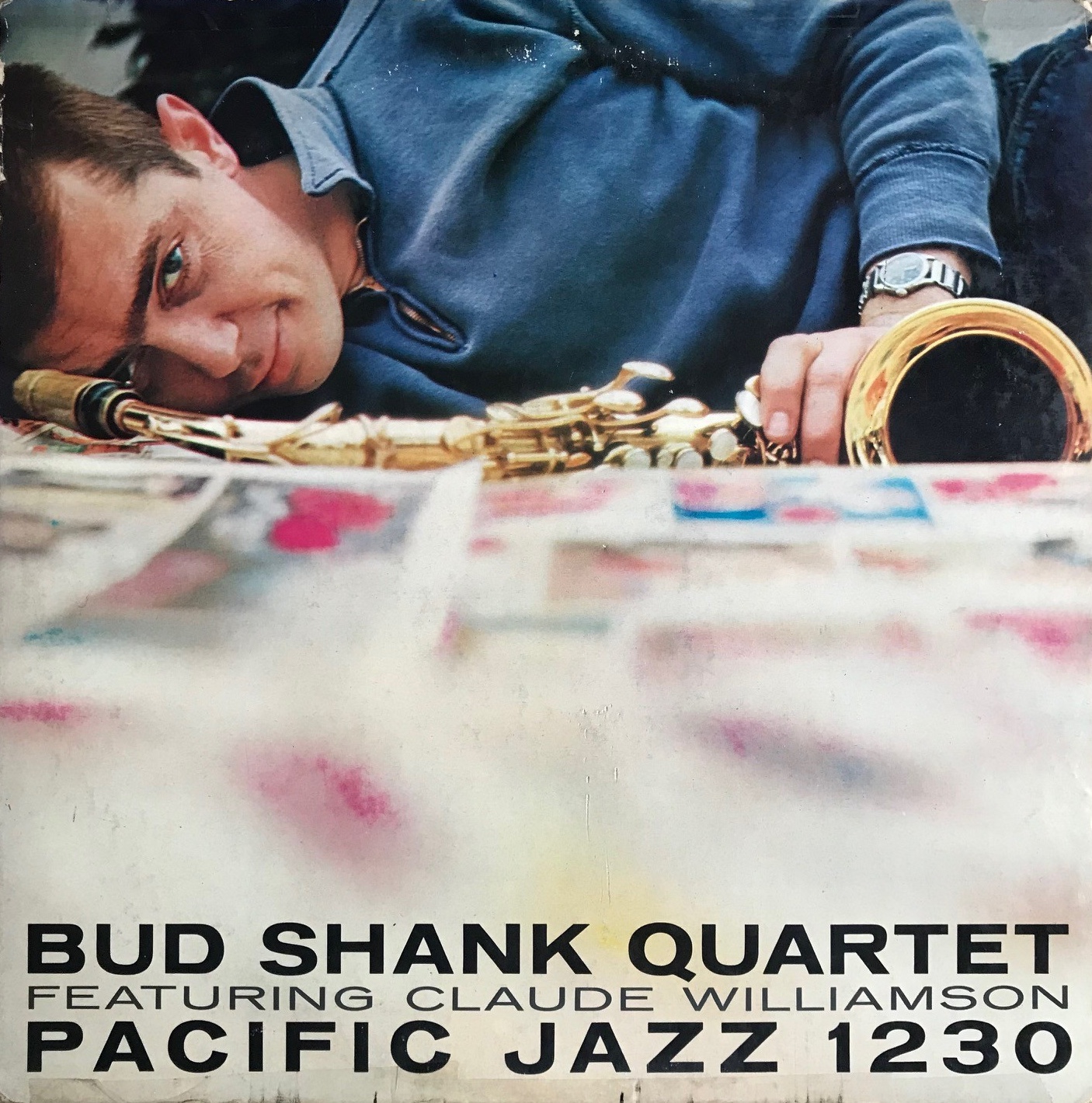

Wisdom comes with age. Guys like Pepper and Shank were like old rocks in the hills of Big Sur. They erode more and more each year, but each new spring season as new flowers come up, the purple and yellow and red bed of blossom seems more beautiful than the preceding year. They played some of their best stuff late in life. Earlier on? Cleaner and calmer, as Ineke states in the case of Shank. But swinging. That’s Bud Shank circa 1956, a clean-cut fellow, almost, but not quite, the boy-next-door. Rising in the ranks in Hollywood, but ready and armed for the real jazz deal.

Highlights? The Lamp Is Low is top-notch, introduced by flute, segueing into fluent swing with alto, and Claude Williamson high on the heels of Shank. These guys gelled very well, like strawberries and whipped cream. Shank’s flute work in the smoothly swinging take on Night In Tunesia is rather stunning. Polka Dots And Moonbeams is turned into a stately fugue. Best of all is Williamson’s unusual Tertia, also classical-tinged, in the introduction, and developing into a kind of bop suite. Walking bass. Flute melody lines. Blues changes. Sassy riffs. Drum break. Then the supple alto madness of Shank and the route on the keys from Powell to Hines by Williamson.

Bud Shank passed away in Tucson, Arizona in 2009.