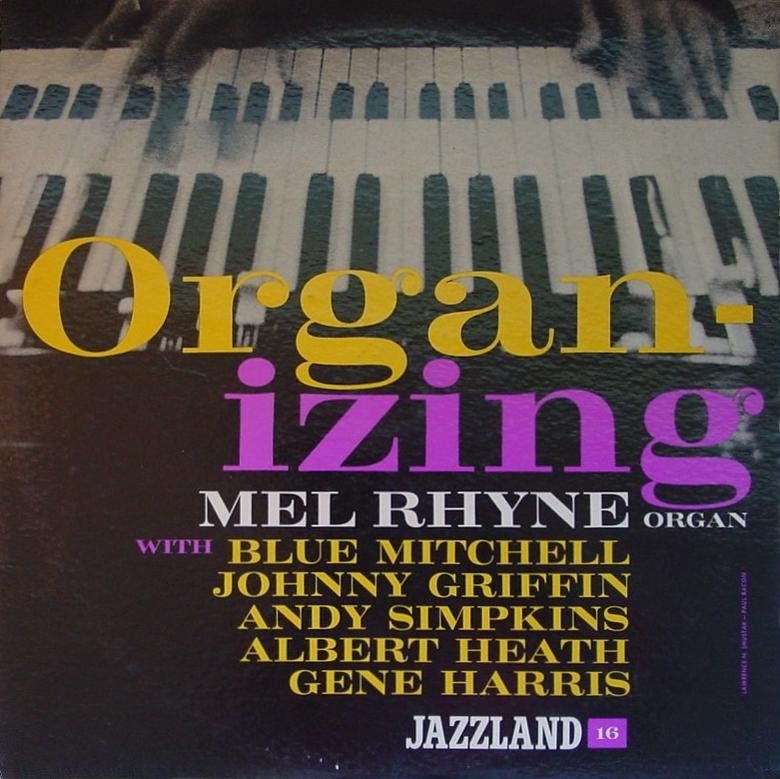

Like a jubilant child eager to play with its long-awaited Santa Claus presents, I gave my recent purchase, Melvin Rhyne’s sought-after solo album from 1960, Organ-Izing, an immediate spin. The organist, best known for his work with guitar legend Wes Montgomery, delivers a tasteful, laid-back blowing session.

Personnel

Melvin Rhyne (organ), Johnny Griffin (tenor saxophone), Blue Mitchell (trumpet), Gene Harris (piano), Andrew Simpkins (bass), Albert Heath (drums)

Recorded

on March 31, 1960 in NYC

Released

as as JLP 16 in 1960

Track listing

Side A:

Things Ain’t What They Used To Be

Blue Farouq

Side B:

Barefoot Sunday Blues

Shoo Shoo Baby

Rhyne was a native of Indianapolis, like Montgomery, who asked him to join his trio in 1959. The organist backed the groundbreaking guitarist on four splendid Riverside albums: Wes Montgomery Trio (1959), Boss Guitar (1963), Portrait Of Wes (1963) and Guitar On The Go (1959/1963). His articulate backing – Rhyne started out as a pianist – matched perfectly with Montgomery’s tasteful style, a coherent mix of melodic single lines, octaves and block chords. Rhyne’s sound on his solo album comes closest to that of the Wes Montgomery Trio album. It has that, as Dutch organist and Rhyne admirer, Arno Krijger, said to me in this interview, unique ‘plucky, percussive sound’. It’s a vibrato-less sound that enabled Rhyne to craft cleanly spun, logical, laid-back lines.

Organ-izing was released on Jazzland, a subsidiary of Riverside. The assembled crew includes two top-rate Riverside artists of the time, Johnny Griffin and Blue Mitchell: guys you can count on for a session of this kind. Griffin is his usual fast-fingered self, grounded in bebop and blues, and peppers his playing with humorous asides. Blue Mitchell stretches out ebulliently on, among others, his own attractive blues line, Blue Farouq.

The album consists of four tunes of the same medium tempo and four beat rhythm, which becomes a bit monotonous after a while. Then again, Rhyne is a mid-tempo maestro. He showed it with Montgomery, deepening considerably, for instance, the groove of Missile Blues on the Portrait Of Wes-album. Medium tempo suits his carefully crafted stories. Rhyne eschews uproaring climaxes and instead creates free-flowing endings, shying away from easy effects. He’s like a minimalist writer. But not just somebody. Rhyne’s the Raymond Carver of the Hammond B3. While reading (listening), one keeps contemplating on the enormously clever usage of deceptively simple language for maximum effect: words and sentences (notes, phrases) carved in stone for the ages.

The unusual combination of piano and organ is uncluttered, largely due to Rhyne’s understated style. Pianist Gene Harris of The Three Sounds trades choruses with Rhyne on all tunes except Shoo Shoo Baby, a feat which underscores the relaxed atmosphere of the proceedings. During such a spontaneous event, one (Harris) cutting short the evolving story of the other (Rhyne) in the mid-slow-draggin’ take on the classic riff Things Ain’t What They Used To Be is part of the charm. Unfazed, Rhyne supports a swinging Harris bit and continues with a solo that’s a lesson in soul and dynamics.

At the end of the decade, Rhyne quit the music business and moved to Wisconsin. He started recording again in the nineties and 00’s, mainly for Criss Cross. Rhyne passed away on March 5, 2013.